California Landlord Law Book V15

Attorneys David Brown & Janet Portman,

& Ralph Warner, J.D.

15th Edition

“ Unblighted by unnecessary legal jargon…this is as necessary

as a rent receipt book or a good repair person.”

LOS ANGELES TIMES

• Deal with tenants legally and effectively

• Avoid lawsuits

• Use a lease designed for California

Free Legal Updates at Nolo.com

The California

Landlord’s Law Book:

Rights &

Responsibilities

OVER

200,000

IN PRINT

DOWNLOAD

FORMS

at nolo.com

is Book Comes

With a Website

DOWNLOAD

FORMS

at nolo.com

Nolo’s award-winning website has a page

dedicated just to this book, where you can:

DOWNLOAD FORMS – All the forms and

worksheets in the book are accessible online

KEEP UP TO DATE – When there are important

changes to the information in this book, we’ll post

updates

READ BLOGS – Get the latest info from Nolo

authors’ blogs

LISTEN TO PODCASTS – Listen to authors discuss

timely issues on topics that interest you

WATCH VIDEOS – Get a quick introduction to a

legal topic with our short videos

You’ll nd the link in the appendix.

And that’s not all.

Nolo.com contains

thousands of articles

on everyday legal and

business issues, plus

a plain-English law

dictionary, all written

by Nolo experts and

available for free. You’ll

also nd more useful

books, software,

online services,

and

downloadable forms.

Get forms and more at

www.nolo.com

LAW for ALL

“ In Nolo you can trust.”

THE NEW YORK TIMES

“ Nolo is always there in a jam as the nation’s premier publisher

of do-it-yourself legal books.”

NEWSWEEK

“ Nolo publications…guide people simply through the how,

when, where and why of the law.”

THE WASHINGTON POST

“ [Nolo’s]…material is developed by experienced attorneys who

have a knack for making complicated material accessible.”

LIBRARY JOURNAL

“ When it comes to self-help legal stuff , nobody does a better job

than Nolo…”

USA TODAY

“ e most prominent U.S. publisher of self-help legal aids.”

TIME MAGAZINE

“ Nolo is a pioneer in both consumer and business self-help

books and software.”

LOS ANGELES TIMES

e Trusted Name

(but don’t take our word for it)

15th Edition

The California

Landlord’s Law Book:

Rights &

Responsibilities

Attorneys David Brown & Janet Portman,

& Ralph Warner, J.D.

LAW for ALL

FIFTEENTH EDITION MARCH 2013

Editor MARCIA STEWART

Cover Design SUSAN PUTNEY

Book Design TERRI HEARSH

Proofreading ROBERT WELLS

Index THÉRÈSE SHERE

Printing BANG PRINTING

ISSN 2163-0313 (print)

ISSN 2326-0114 (online)

ISBN 978-1-4133-1853-1 (pbk)

ISBN 978-1-4133-1854-8 (epub ebook)

This book covers only United States law, unless it specifically states otherwise.

Copyright © 1986, 1989, 1990, 1993, 1994, 1996, 1997, 2000, 2002, 2004, 2005, 2007, 2009,

2011, and 2013 by David Brown. All rights reserved. The NOLO trademark is registered

in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Printed in the U.S.A.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or

otherwise without prior written permission. Reproduction prohibitions do not apply to the

forms contained in this product when reproduced for personal use. For information on

bulk purchases or corporate premium sales, please contact the Special Sales Department.

Call 800-955-4775 or write to Nolo, 950 Parker Street, Berkeley, California 94710.

Please note

We believe accurate, plain-English legal information should help you solve many of

your own legal problems. But this text is not a substitute for personalized advice from

a knowledgeable lawyer. If you want the help of a trained professional—and we’ll

always point out situations in which we think that’s a good idea—consult an attorney

licensed to practice in your state.

About the Authors

David Brown practices law in the Monterey, California, area, where he has

represented both landlords and tenants in hundreds of court cases—most of which

he felt could have been avoided if both sides were more fully informed about

landlord/tenant law. Brown, a graduate of Stanford University (chemistry) and the

University of Santa Clara Law School, is the author of Fight Your Ticket & Win in

California, Beat Your Ticket: Go to Court & Win, and The California Landlord’s Law

Book: Evictions, and the coauthor of The Guardianship Book for California.

Ralph Warner is founder and publisher of Nolo, and an expert on landlord/tenant

law. Ralph has been a landlord, a tenant, and, for several years, a property manager.

Having become fed up with all these roles, he bought a single-family house.

Janet Portman, an attorney and Nolo’s Co-Executive Editor, received under graduate

and graduate degrees from Stanford and a law degree from Santa Clara University.

She is an expert on landlord/tenant law and the coauthor of Every Landlord’s Legal

Guide, Every Landlord’s Guide to Finding Great Tenants, Every Tenant’s Legal Guide,

Renters’ Rights, Leases & Rental Agreements, and Negotiate the Best Lease for Your

Business. Janet writes a nationally syndicated column on landlord-tenant issues,

“Rent It Right,” which appears in the Chicago Tribune and The Boston Globe, among

other newspapers.

Table of Contents

e California Landlord’s Legal Companion .................................................................. 1

California-Specific Legal Information ............................................................................................................ 1

California Legal Forms and Notices ............................................................................................................... 1

California Rent Control Rules ........................................................................................................................... 1

How (and Why) to Use is Book ................................................................................................................... 2

Evicting a Tenant .................................................................................................................................................... 2

Renting Out a Condo or Townhouse ............................................................................................................ 2

Who Should Not Use is Book ...................................................................................................................... 2

1

Renting Your Property: How to Choose Tenants

and Avoid Legal Pitfalls

........................................................................................................................ 5

Adopt a Rental Plan and Stick to It ................................................................................................................ 6

Advertising Rental Property .............................................................................................................................. 6

Dealing With Prospective Tenants ................................................................................................................. 7

Checking Background, References, and Credit History of Potential Tenants ...........................16

Choosing—And Rejecting—An Applicant ...............................................................................................22

Holding Deposits ..................................................................................................................................................26

2

Understanding Leases and Rental Agreements .......................................................29

Oral Agreements Are Not Recommended ...............................................................................................31

Written Agreements: Which Is Better, a Lease or a Rental Agreement? .....................................32

Foreign Language Note on California Leases and Rental Agreements ........................................35

Common Legal Provisions in Lease and Rental Agreement Forms ...............................................36

How to Modify and Sign Form Agreements............................................................................................54

Cosigners .................................................................................................................................................................. 58

Illegal Lease and Rental Agreement Provisions .......................................................................................60

3

Basic Rent Rules ..........................................................................................................................................65

How Much Can You Charge? ..........................................................................................................................66

When Rent Is Due ................................................................................................................................................66

Where and How Rent Is Due...........................................................................................................................68

Late Charges ...........................................................................................................................................................69

Returned Check Charges ..................................................................................................................................71

Partial Rent Payments ........................................................................................................................................ 71

4

Rent Control ..................................................................................................................................................75

Property Exempt From Rent Control..........................................................................................................77

Local Rent Control Administration .............................................................................................................77

Registration of Rental Properties ..................................................................................................................77

Rent Formula and Individual Adjustments ..............................................................................................78

Security Deposits .................................................................................................................................................79

Certification of Correct Rent Levels by Board .........................................................................................79

Vacancy Decontrol .............................................................................................................................................. 80

Tenant Protections: Just Cause Evictions ..................................................................................................80

Rent Control Board Hearings ..........................................................................................................................83

Legal Sanctions for Violating Rent Control ..............................................................................................86

5

Security Deposits ...................................................................................................................................... 89

Security Deposits Must Be Refundable ...................................................................................................... 90

How Landlords May Use Deposits ...............................................................................................................91

Dollar Limits on Deposits ................................................................................................................................. 91

How to Increase Deposit Amounts .............................................................................................................92

Last Month’s Rent ................................................................................................................................................92

Interest, Accounts, and Record Keeping on Deposits .........................................................................93

Insurance as a Backup to Deposits ............................................................................................................... 95

When Rental Property Is Sold ........................................................................................................................95

When You’re Purchasing Rental Property .................................................................................................96

6

Property Managers ................................................................................................................................. 99

Hiring Your Own Manager ............................................................................................................................100

Avoiding Legal Problems................................................................................................................................ 101

Management Companies ...............................................................................................................................111

An Owner’s Liability for a Manager’s Acts .............................................................................................. 112

Notifying Tenants of the Manager .............................................................................................................113

Firing a Manager .................................................................................................................................................114

Evicting a Manager ............................................................................................................................................114

7

Getting the Tenant Moved In ....................................................................................................117

Inspect and Photograph the Unit ...............................................................................................................118

Send New Tenants a Move-In Letter ........................................................................................................ 125

First Month’s Rent and Security Deposit Checks ................................................................................129

8

Lawyers, Legal Research, Eviction Services, and Mediation ......................131

Legal Research Tools ........................................................................................................................................132

Mediating Disputes With Tenants ..............................................................................................................135

Nonlawyer Eviction Services ........................................................................................................................ 136

Finding a Lawyer .................................................................................................................................................137

Paying a Lawyer .................................................................................................................................................. 138

Resolving Problems With Your Lawyer ....................................................................................................139

9

Discrimination...........................................................................................................................................141

Legal Reasons for Refusing to Rent to a Tenant ...................................................................................142

Sources of Discrimination Laws .................................................................................................................. 146

Forbidden Types of Discrimination ............................................................................................................147

Occupancy Limits ..............................................................................................................................................161

Legal Penalties for Discrimination ............................................................................................................. 163

Owner-Occupied Premises and Occasional Rentals ......................................................................... 164

Managers and Discrimination ..................................................................................................................... 165

Insurance Coverage for Discrimination Claims ................................................................................... 165

10

Cotenants, Subtenants, and Guests ................................................................................... 169

Renting to More an One Tenant ............................................................................................................170

Subtenants and Sublets ...................................................................................................................................171

When a Tenant Brings in a Roommate .................................................................................................... 173

If a Tenant Leaves and Assigns the Lease to Someone ......................................................................174

11

e Landlord’s Duty to Repair and Maintain the Property ...................... 177

State and Local Housing Standards .......................................................................................................... 179

Enforcement of Housing Standards ..........................................................................................................180

Maintenance of Appliances and Other Amenities ............................................................................ 183

e Tenant’s Responsibilities ....................................................................................................................... 184

e Tenant’s Right to Repair and Deduct .............................................................................................. 185

e Tenant’s Right to Withhold Rent When the Premises Aren’t Habitable ......................... 186

e Landlord’s Options If a Tenant Repairs and Deducts or Withholds Rent ....................... 188

e Tenant’s Right to Move Out .................................................................................................................191

e Tenant’s Right to Sue for Defective Conditions ......................................................................... 193

Avoid Rent Withholding and Other Tenant Remedies by Adopting a High-Quality Repair

and Maintenance System

.......................................................................................................................... 196

Tenant Updates and Landlord’s Regular Safety and Maintenance Inspections .................... 202

Tenants’ Alterations and Improvements ................................................................................................ 205

Cable TV ................................................................................................................................................................209

Satellite Dishes and Other Antennas ....................................................................................................... 209

12

e Landlord’s Liability for Dangerous Conditions,

Criminal Acts, and Environmental Health Hazards

...........................................215

Legal Standards for Liability ..........................................................................................................................217

Landlord’s Responsibility to Protect Tenants From Crime ............................................................. 224

How to Protect Your Tenants From Criminal Acts While Also Reducing Your Potential

Liability

............................................................................................................................................................... 229

Protecting Tenants From Each Other (and From the Manager) .................................................. 235

Landlord Liability for Drug-Dealing Tenants ......................................................................................... 237

Liability for Environmental Hazards ......................................................................................................... 240

Liability, Property, and Other Types of Insurance .............................................................................. 263

13

e Landlord’s Right of Entry and Tenant’s Privacy .......................................... 269

e Landlord’s Right of Entry ...................................................................................................................... 270

Entry by Others .................................................................................................................................................. 277

Other Types of Invasions of Privacy .......................................................................................................... 278

What to Do When Tenants Are Unreasonable .................................................................................... 279

Tenants’ Remedies If a Landlord Acts Illegally .....................................................................................280

14

Raising Rents and Changing Other Terms of Tenancy ................................... 283

Basic Rules to Change or End a Tenancy ................................................................................................284

Rent Increase Rules ...........................................................................................................................................284

Preparing a Notice to Raise Rent ................................................................................................................290

How to Serve the Notice on the Tenant ................................................................................................. 293

When the Rent Increase Takes Effect .......................................................................................................294

Changing Terms Other an Rent ............................................................................................................295

15

Retaliatory Rent Increases and Evictions .....................................................................299

Types of Prohibited Retaliation ...................................................................................................................300

Proving Retaliation ........................................................................................................................................... 301

Avoiding Charges of Retaliation ................................................................................................................. 302

Liability for Illegal Retaliation ......................................................................................................................305

16

e ree-Day Notice to Pay Rent or Quit .................................................................309

When to Use a ree-Day Notice to Pay Rent or Quit .....................................................................310

How to Determine the Amount of Rent Due .......................................................................................310

Directions for Completing the ree-Day Notice to Pay Rent or Quit .....................................313

Serving the ree-Day Notice on the Tenant ........................................................................................314

When the Tenant Offers to Pay Rent ........................................................................................................318

e Tenant Moves Out ....................................................................................................................................318

If the Tenant Won’t Pay Rent (or Leave)...................................................................................................319

17

Self-Help Evictions, Utility Terminations, and

Taking Tenants’ Property

...............................................................................................................321

Forcible Evictions ..............................................................................................................................................322

Blocking or Driving the Tenant Out Without Force..........................................................................323

Seizing the Tenant’s Property and Other Harassment ......................................................................324

Effect of Landlord’s Forcible Eviction on a Tenant’s Liability for Rent ........................................324

18

Terminating Tenancies .................................................................................................................... 327

e 30-, 60-, or 90-Day Notice .................................................................................................................... 329

e ree-Day Notice in Cities at Don’t Require Just Cause for Eviction .......................... 337

Termination When Just Cause for Eviction Is Required ...................................................................344

Termination Without Notice ...................................................................................................................... 353

e Initial Move-Out Inspection Notice ................................................................................................ 353

19

When a Tenant Leaves: Month-to-Month Tenancies,

Fixed-Term Leases, Abandonment, and Death of a Tenant

...................... 357

Terminating Month-to-Month Tenancies.............................................................................................. 358

Terminating Fixed-Term Leases ...................................................................................................................360

Termination by Tenant Abandoning Premises ....................................................................................364

What to Do When Some Tenants Leave and Others Stay ..............................................................367

Death of a Tenant .............................................................................................................................................368

20

Returning Security Deposits ...................................................................................................... 373

Basic Rules for Returning Deposits ............................................................................................................ 375

Initial Move-Out Inspection and Tenant’s Right to Receipts ........................................................ 376

Final Inspection .................................................................................................................................................. 385

Deductions for Cleaning and Damages ...................................................................................................386

Deductions for Unpaid Rent ........................................................................................................................387

Preparing an Itemized Statement of Deductions ............................................................................... 389

Small Claims Lawsuits by the Tenant ....................................................................................................... 394

If the Deposit Doesn’t Cover Damage and Unpaid Rent .................................................................399

21

Property Abandoned by a Tenant ....................................................................................... 403

Handling, Storing, and Disposing of Personal Property ...................................................................404

Motor Vehicles Left Behind ..........................................................................................................................408

Appendixes

A

Rent Control Chart ...............................................................................................................................411

Reading Your Rent Control Ordinance ...................................................................................................412

Finding Municipal Codes and Rent Control Ordinances Online .................................................. 413

Rent Control Rules by California City .......................................................................................................415

B

How to Use the Interactive Forms on the Nolo Website ............................. 445

Editing RTFs .........................................................................................................................................................446

List of Forms Available on the Nolo Website .......................................................................................446

Index ...........................................................................................................................................................................449

e California Landlord’s Legal Companion

H

ere is a concise legal guide for people who

own or manage residential rental property in

California. It has two main goals: to explain

California landlord/tenant law in as straightforward

a manner as possible, and to help you use this legal

knowledge to anticipate and, where possible, avoid

legal problems.

California-Specific

Legal Information

This book concentrates on the dozens of state legal

rules associated with most aspects of renting and

managing residential real property. For example, we

include information on leases, rental agreements,

managers, credit checks, security deposits, discrimi-

nation, invasion of privacy, the landlord’s duty to

maintain the premises (and tenant rights if you don’t),

liability for tenant exposure to mold, how to deal with

bedbugs, how to increase the rent or terminate for

nonpayment of rent, what you can legally do with a

tenant’s abandoned property, and much more. This

book also covers key federal laws that affect landlords,

such as lead-paint disclosure rules, and highlights

important local rules, particularly rent control (see

below) and health and safety standards.

California Legal Forms

and Notices

We provide over 40 practical, easy-to-use, and legal

forms, notices, letters, and checklists throughout this

book, including rental applications, leases, repair

notices, warning letters, notice of entry forms, security

deposit itemizations, move-in and move-out letters,

disclosure forms, three-day nonpayment of rent

and other termination notices, and more. We clearly

explain what form you need for different situations,

with clear instructions on how to prepare the form

(including how to provide proper legal notice when

required). We also provide filled-in samples in the text.

All forms are available for download on the Nolo

website on a special companion page for this book as

described below.

TIP

Put it in writing. Using the forms, checklists,

and notices included in this book will help you avoid legal

problems in the first place, and minimize those that can’t be

avoided. e key is to establish a good paper trail for each

tenancy, beginning with the rental agreement and lease

through a termination notice and security deposit itemization.

Such documentation is often legally required and will be

extremely valuable if attempts at resolving disputes with your

tenant fail.

California Rent Control Rules

Many of you will own rental properties in areas

covered by rent control ordinances. These laws not

only establish how much you can charge for most

residential living spaces, they also override state

law in a number of other ways. For example, many

rent control ordinances restrict a landlord’s ability

to terminate month-to-month tenancies by requiring

“just cause for eviction.” We handle rent control

in three ways: First, as we explain your rights and

responsibilities under state law in the bulk of this

book, we indicate those areas in which rent control

laws are likely to modify or change these rules.

Second, we provide a detailed discussion of rent

control in Chapter 4. Third, we provide summaries

(see Appendix A) of key rent control rules, particularly

how they affect evictions, in 16 California cities with

rent control. If you own rental property in a rent

control city, it’s crucial that you have a current copy of

2

|

THE CALIFORNIA LANDLORD’S LAW BOOK: RIGHTS & RESPONSIBILITIES

the local ordinance. You can get a copy from your city

rent control board or online.

How (and Why) to Use is Book

This book provides a roughly chronological treatment

of subjects important to landlords—beginning with

taking rental applications and ending with returning

security deposits when a tenant moves out. But you

shouldn’t wait until a problem happens to educate

yourself about the law.

With sensible planning, you can either minimize—

or avoid—the majority of serious legal problems

encountered by landlords. For example, in Chapter 11

we show you how to plan ahead to deal with those

few tenants who will inevitably try to invent bogus

reasons why they were legally entitled to withhold

rent. Similarly, in Chapter 9 we discuss ways to be sure

that you, your managers, and other employees know

and follow antidiscrimination laws and, at least as

important, make it clear that you are doing so. We take

you through most of the important tasks of being a

landlord. Most of these tasks you can do yourself, but

we are quick to point out situations when an attorney’s

help will be useful or necessary.

We believe that in the long run a landlord is best

served by establishing a positive relationship with

tenants. Why? First, because it’s our personal view

that adherence to the law and principles of fairness

is a good way to live. Second, your tenants are

your most important economic asset and should be

treated as such. Think of it this way: From a long-

term perspective, the business of renting residential

properties is often less profitable than is cashing in

on the appreciation of that property. Your tenants are

crucial to this process, since it is their rent payments

that allow you to carry the cost of the real property

while you wait for it to go up in value. And just as

other businesses place great importance on conserving

natural resources, it makes sense for you to adopt

legal and practical strategies designed to establish and

maintain a good relationship with your tenants.

Evicting a Tenant

This book, The California Landlord’s Law Book: Rights

& Responsibilities, is the first of a two-volume set. It

explains how to terminate a tenancy, but if you need

to evict a tenant, you’ll want to consult the second

volume, The California Landlord’s Law Book: Evictions.

The Evictions volume provides a step-by-step guide

and all the necessary forms and instructions for ending

a tenancy and doing your own evictions.

Renting Out a Condo

or Townhouse

If you are renting out your condominium or town-

house, use this book in conjunction with your

homeowners’ association’s CC&Rs (covenants,

conditions, and restrictions). These rules may affect how

you structure the terms and conditions of the rental

and how your tenants may use the unit. For example,

many homeowners’ associations control the number

of vehicles that can be parked on the street. If your

association has a rule like this, your renters will need to

comply with it, and you cannot rent to tenants with too

many vehicles without running afoul of the rules.

You need to be aware that an association rule

may be contrary to federal, state, or local law. For

instance, an association rule that banned all persons

of a certain race or religion from the property would

not be upheld in court. And owners of condominium

units in rent-controlled areas must comply with the

ordinance, regardless of association rules to the

contrary. Unfortunately, it’s not always easy to know

whether an association rule will pass legal muster. To

know whether a particular rule is legally permissible is

an inquiry that, in some cases, is beyond the scope of

this book.

Who Should Not Use is Book

Do not use this book or forms in the following

situations

•Renting commercial property for your business. Legal

rules and practices vary widely for commercial

rentals—from how rent is set to the length and

terms of leases.

•Renting out a space or unit in a mobile home park or

marina. Different rules often apply. For details,

check out the California Department of Housing

and Community Development publication, 2012

THE CALIFORNIA LANDLORD’S LEGAL COMPANION|3

Mobilehome Residency Law, available at www.hcd.

ca.gov/codes/mp/2012MRL.pdf.

•Renting out a live/work unit (such as a loft). While

you will be subject to state laws governing

residential units, you may have additional

requirements (imposed by building codes) that

pertain to commercial property as well. Check

with your local building inspector’s office for the

rules governing live/work units.

Get Updates, Forms, and More at This

Book’s Companion Page on Nolo.com

You can download the lease, rental agreement, and all

of the other forms and agreements in this book at:

www.nolo.com/back-of-book/LBRT.html

When there are important changes to the information

in this book, we’ll post updates on this same dedicated

page (what we call the book’s companion page). You‘ll

find other useful information on this page, too, such as

author blogs, podcasts, and videos. See the end of the

table of contents for a complete list of forms available

on nolo.com.

Abbreviations Used in This Book

We make frequent references to the California Civil

Code (CC) and the California Code of Civil Procedure

(CCP), important statutes that set out landlords’ rights

and responsibilities. We use the following standard

abbreviations throughout this book for these and other

important statutes and court cases covering landlord

rights and responsibilities. ere are many times when you

will surely want to refer to the complete statute or case.

See Chapter 8 for advice on how to find a specific statute

or case and do legal research.

California Codes

CC Civil Code

CCP Code of Civil Procedure

UHC Uniform Housing Code

B&P Business and Professions Code

H&S Health and Safety Code

CCR California Code of Regulations

Ed. Code Education Code

Federal Laws

U.S.C. United States Code

Cases

Cal. App. California Court of Appeal

Cal. Rptr. California Court of Appeal and

California Supreme Court

Cal. California Supreme Court

F. Supp. United States District Court

F.2d, F.3d United States Court of Appeal

U.S. United States Supreme Court

Opinions

Ops. Cal. Atty. Gen. California Attorney General Opinions

l

CHAPTER

1

Renting Your Property: How to Choose

Tenants and Avoid Legal Pitfalls

Adopt a Rental Plan and Stick to It ................................................................................................................... 6

Advertising Rental Property ..................................................................................................................................6

Dealing With Prospective Tenants ....................................................................................................................7

e Rental Application ........................................................................................................................................7

Credit Check and Screening Fees .................................................................................................................12

Terms of the Rental ..............................................................................................................................................12

Landlord Disclosures ...........................................................................................................................................13

Checking Background, References, and Credit History of Potential Tenants ...................... 16

Check With Previous Landlords and Other References .................................................................. 16

Verify a Potential Tenant’s Income and Employment .......................................................................17

Obtain a Credit Report From a Credit Reporting Agency ..............................................................17

See If Any “Tenant-Reporting Services” Operate in Your Area .................................................... 21

Check With the Tenant’s Bank to Verify Account Information .................................................. 21

Review Court Records ........................................................................................................................................ 21

Checking the Megan’s Law Database ........................................................................................................ 22

Do Not Request Proof of, or Ask About, Immigration Status .....................................................22

Choosing—And Rejecting—An Applicant ................................................................................................ 22

Record Keeping......................................................................................................................................................23

Information You Must Provide Rejected Applicants .........................................................................24

Holding Deposits ....................................................................................................................................................... 26

FORMS IN THIS CHAPTER

Chapter 1 includes instructions for and samples of the following forms:

• Rental Application

• Consent to Background and Reference Check

• Application Screening Fee Receipt

• Disclosures by Property Owner(s)

• Tenant References

• Notice of Denial Based on Credit Report or Other Information, and

• Receipt and Holding Deposit Agreement.

e Nolo website includes downloadable copies of these forms. See Appendix B for the link

to the forms in this book.

6

|

THE CALIFORNIA LANDLORD’S LAW BOOK: RIGHTS & RESPONSIBILITIES

A

ll landlords typically follow the same process

when renting property. We recognize that a

landlord with 40 (or 400) units has different

business challenges than a person with an in-law

cottage in the backyard or a duplex around the corner.

Still, the basic process of filling rentals remains the

same:

•Decide the terms of your rental, including rent,

deposits, and the length of the tenancy.

•Advertise your property.

•Accept applications.

•Screen potential tenants.

•Choose someone to rent your property.

In this chapter, we examine the practical and legal

aspects of each of these steps, with an eye to avoiding

several common legal problems. Because the topic

of discrimination is so important we devote a whole

chapter to it later in the book (Chapter 9), including

advice on how to avoid discrimination in your tenant

selection process.

RESOURCE

For comprehensive information and over

40 forms on advertising, showing your rental, screening

applicants, and accepting and rejecting prospects, see Every

Landlord’s Guide to Finding Great Tenants, by Janet Portman

(Nolo).

Adopt a Rental Plan

and Stick to It

Before you advertise your property for rent, you’ll

want to make some basic decisions, which will form

the backbone of your lease or rental agreement—how

much rent to charge, when it is payable, whether to

offer a fixed-term lease or a month-to-month tenancy,

and how much of a security deposit to require. You’ll

also need to decide the responsibilities of a manager (if

any) in renting out your property.

RELATED TOPIC

If you haven’t made these important decisions,

the details you need are in Chapters 2, 3, 5, and 6.

In renting residential property, be consistent when

dealing with prospective tenants. The reason for this

is simple: If you don’t treat all tenants more or less

equally—for example, if you arbitrarily set tougher

standards for renting to a racial minority—you are

violating federal laws and opening yourself up to

lawsuits.

Of course, there will be times when you will want

to bargain a little with a prospective tenant—for

example, you may let a tenant have a cat in exchange

for paying a higher security deposit (as long as it

doesn’t exceed the legal limits set by law). As a general

rule, however, you’re better off figuring out your rental

plan in advance and sticking to it.

Advertising Rental Property

In some areas, landlords are lucky enough to fill all

vacancies by word of mouth. If you fit this category,

skip to the next section.

There is one crucial point you should remember

about advertising: Where you advertise is more

important than how you advertise. For example, if you

rent primarily to college students, your best bet is the

campus newspaper or housing office. Whether you

simply put a sign in front of your apartment building,

post a notice on Craigslist, or work with a rental

service or property management company, be sure

the way you advertise reaches a sufficient number of

the sort of people who are likely to meet your rental

criteria.

Legally, you should have no trouble if you follow

these simple rules:

Make sure the price in your ad is an honest one. If a

tenant shows up promptly and agrees to all the terms

set out in your ad, you may run afoul of the law if you

arbitrarily raise the price. This doesn’t mean you are

always legally required to rent at your advertised price,

however. If a tenant asks for more services or different

lease terms, which you feel require more rent, it’s fine

to bargain and raise your price. And if competing

tenants begin a bidding war, there’s nothing illegal

about accepting more rent—as long as it is truly freely

offered. However, be sure to abide by any applicable

rent limits in local rent control areas.

Don’t advertise something you don’t have. Some large

landlords, management companies, and rental services

have advertised units that weren’t really available

in order to produce a large number of prospective

ChApter 1 |RENTING YOUR PROPERTY

|

7

tenants who could then be “switched” to higher-priced

or inferior units. This type of advertising is illegal, and

many property owners have been prosecuted for bait-

and-switch practices.

Be sure your ad can’t be construed as discriminatory. Ads

should not mention age, sex, race, religion, disability,

or adults-only—unless yours is senior citizens’

housing. (Senior citizens’ housing must comply with

CC § 51.3. Namely, it must be reserved for persons

over age 62, or be a complex of 150 or more units (35

in nonmetropolitan areas) for persons over age 55.)

Neither should ads imply through words, photographs,

illustrations, or language that you prefer or discriminate

against renters because of their age, sex, race, and so

on. For example, if your property is in a mixed Chinese

and Hispanic neighborhood and if you advertise

only in Spanish, you may be courting a fair housing

complaint. In addition, any discrimination against any

group that is unrelated to a legitimate landlord concern

is illegal. For example, it’s discriminatory to refuse to

rent to unmarried couples, because the legal status of

their relationship has nothing to do with whether they

will be good, stable tenants.

exAmple: An ad for an apartment that says

“Young, female student preferred” is illegal,

since sex and age discrimination are forbidden

by both state and federal law. Under California

law, discrimination based on the prospective

tenant’s occupation also is illegal, since there is no

legitimate business reason to prefer tenants with

certain occupations over others.

If you have any legal and nondiscriminatory rules on

important issues, such as no pets, it’s a good idea to put

them in your ad. This will weed out those applicants

who don’t like your terms. But even if you don’t

include a “no pets” clause, you won’t be obligated to

rent to applicants with pets. You can still announce the

policy at the time you interview a prospective tenant—

and you can use your discretion when deciding

whether their pets are acceptable.

Dealing With Prospective Tenants

It’s good business, as well as a sound legal protection

strategy, to develop a system for screening prospective

tenants. Whether you handle reference checking and

other tasks yourself or hire a manager or property

management company, your goal is the same—to

select tenants who will pay their rent on time, keep

their rental in good condition, and not cause you any

legal or practical hassles later.

TIP

Never, never let anyone stay in your property

on a temporary basis. Even if you haven’t signed a rental

agreement or accepted rent, giving a person a key or allowing

him or her to move in as much as a toothbrush can give that

person the legally protected status of a tenant. en, if the

person won’t leave voluntarily, you will have to file a lawsuit to

evict him or her.

e Rental Application

Each prospective tenant—everyone age 18 or older

who wants to live in your rental property—should fill

out a written application. This is true whether you’re

renting to a married couple sharing an apartment or to

a number of unrelated roommates.

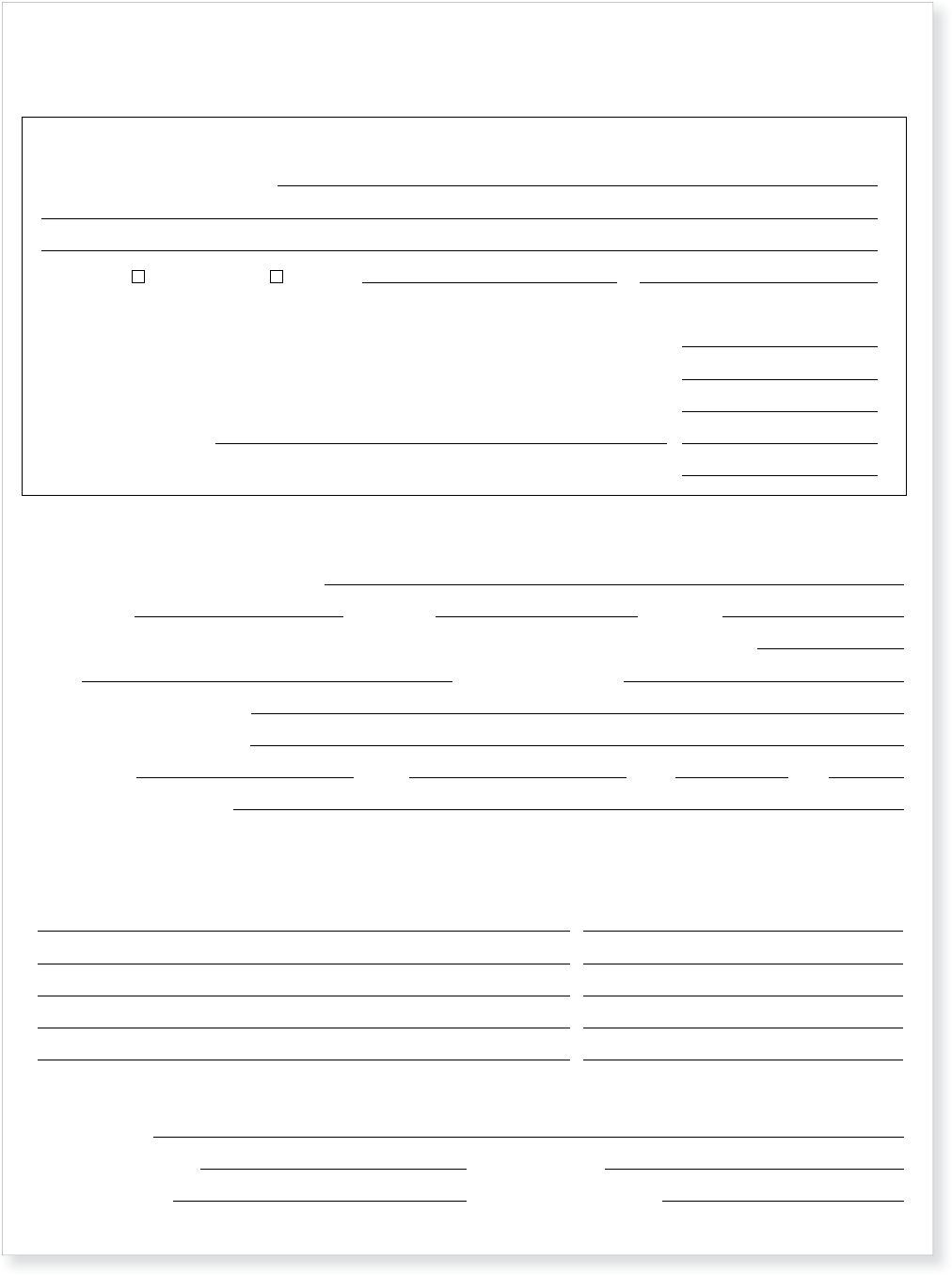

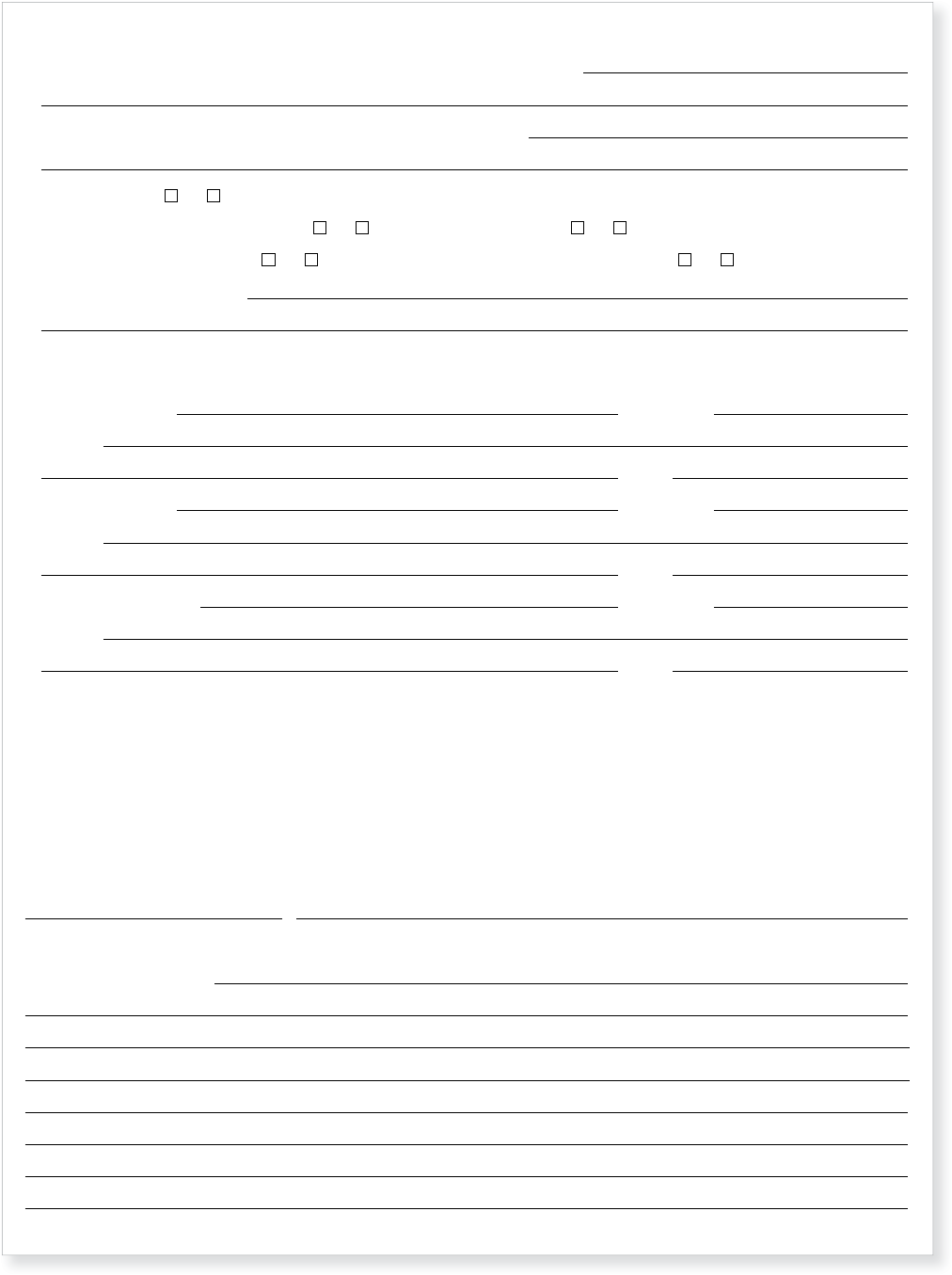

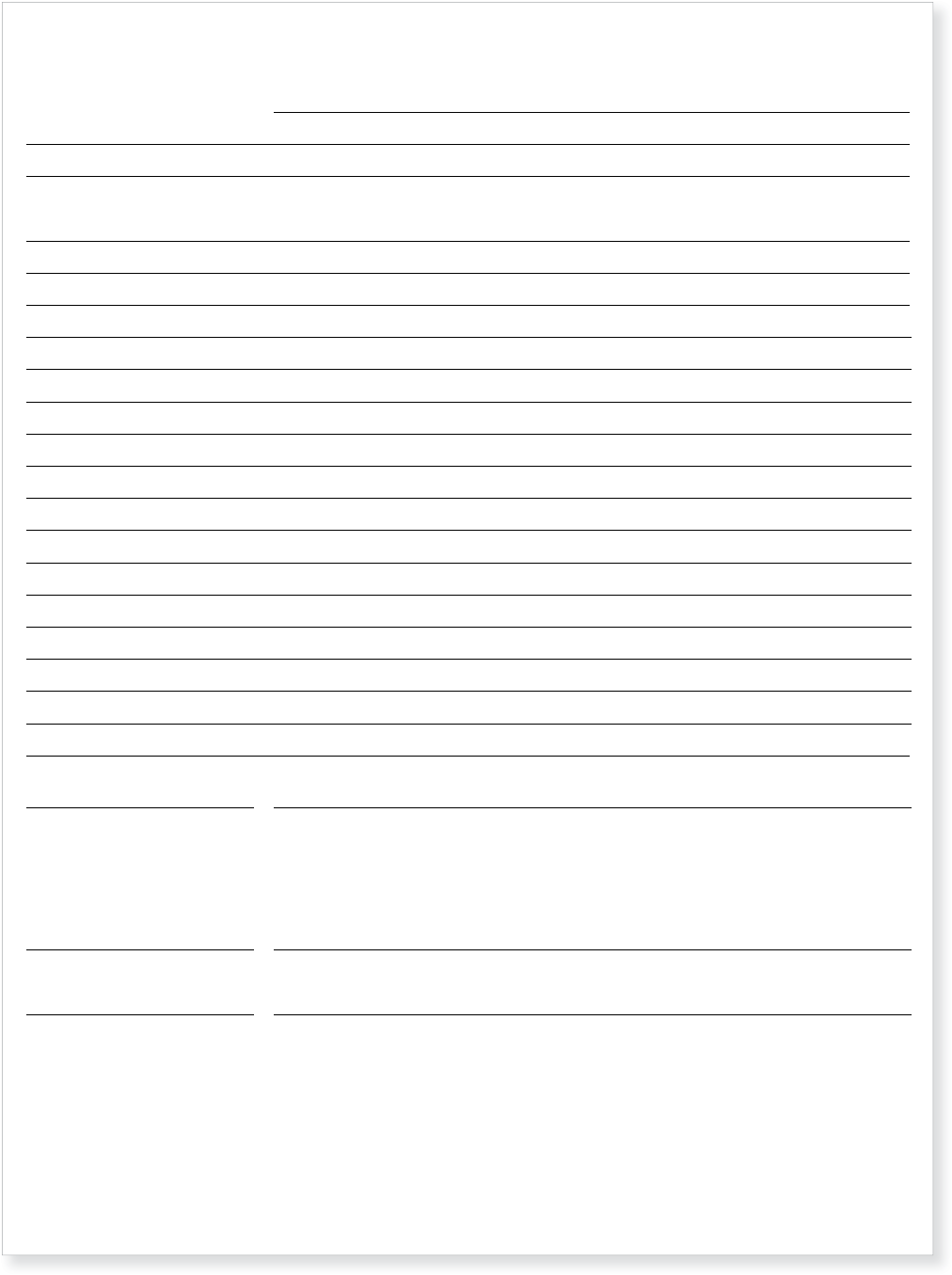

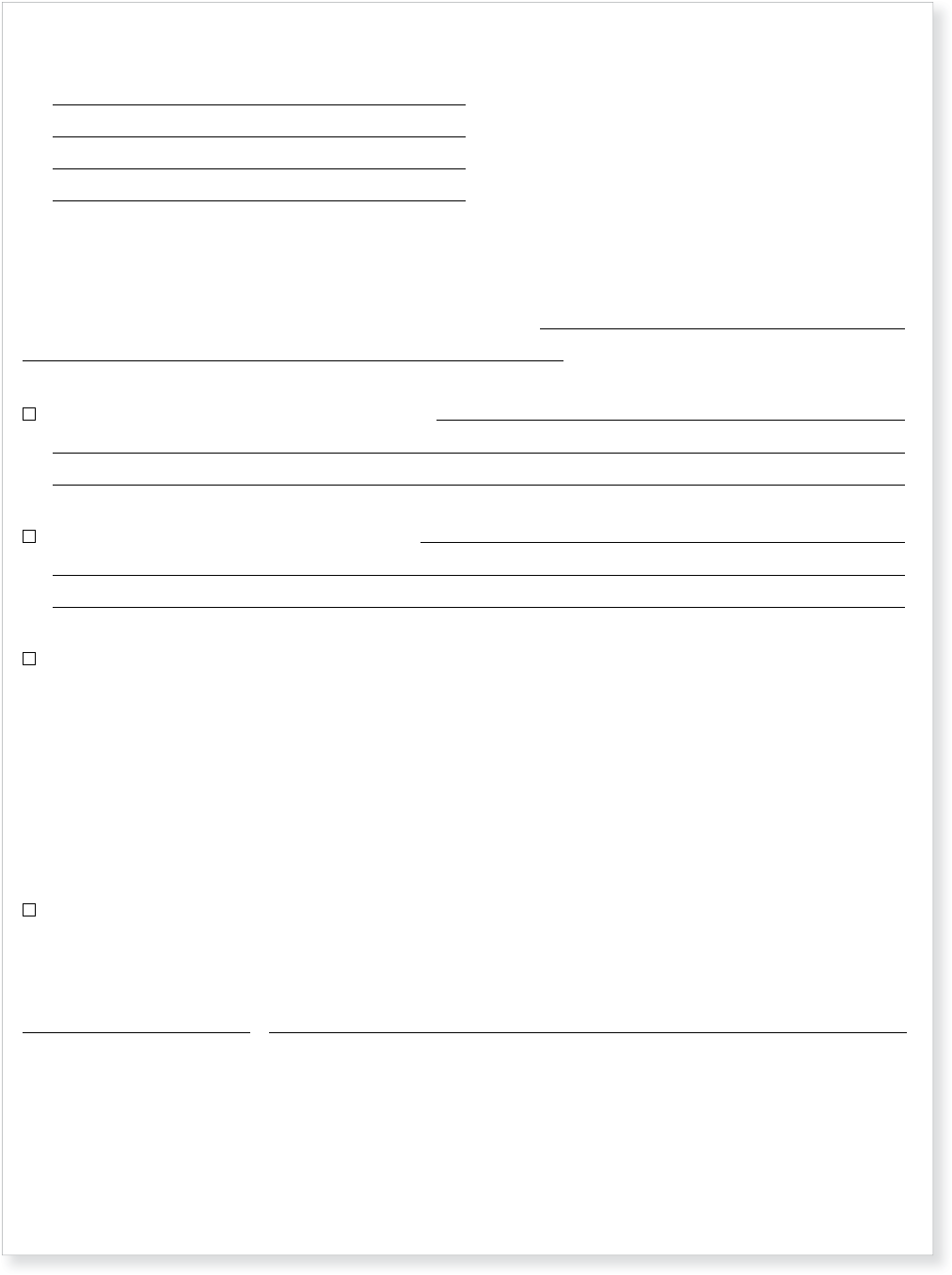

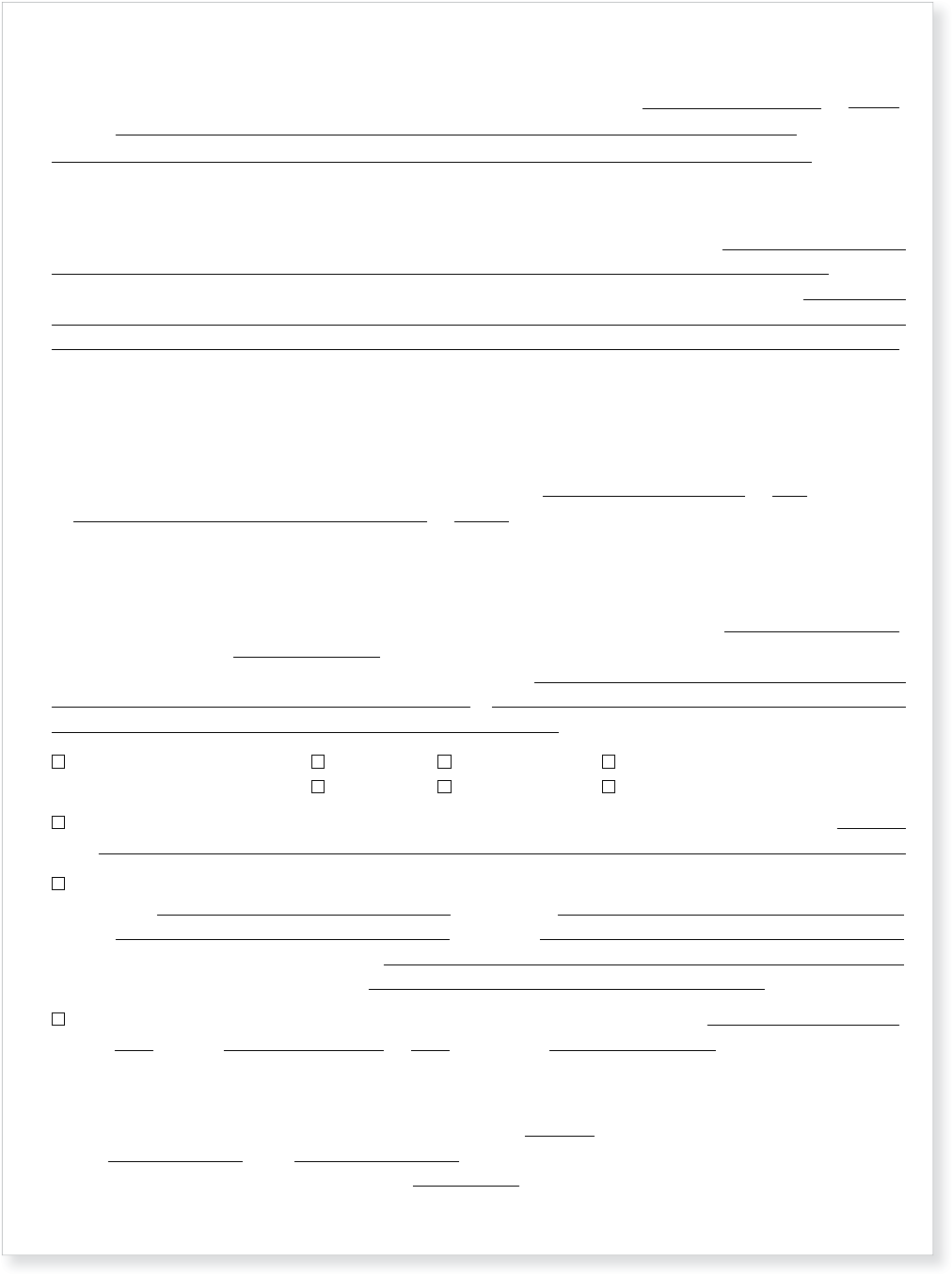

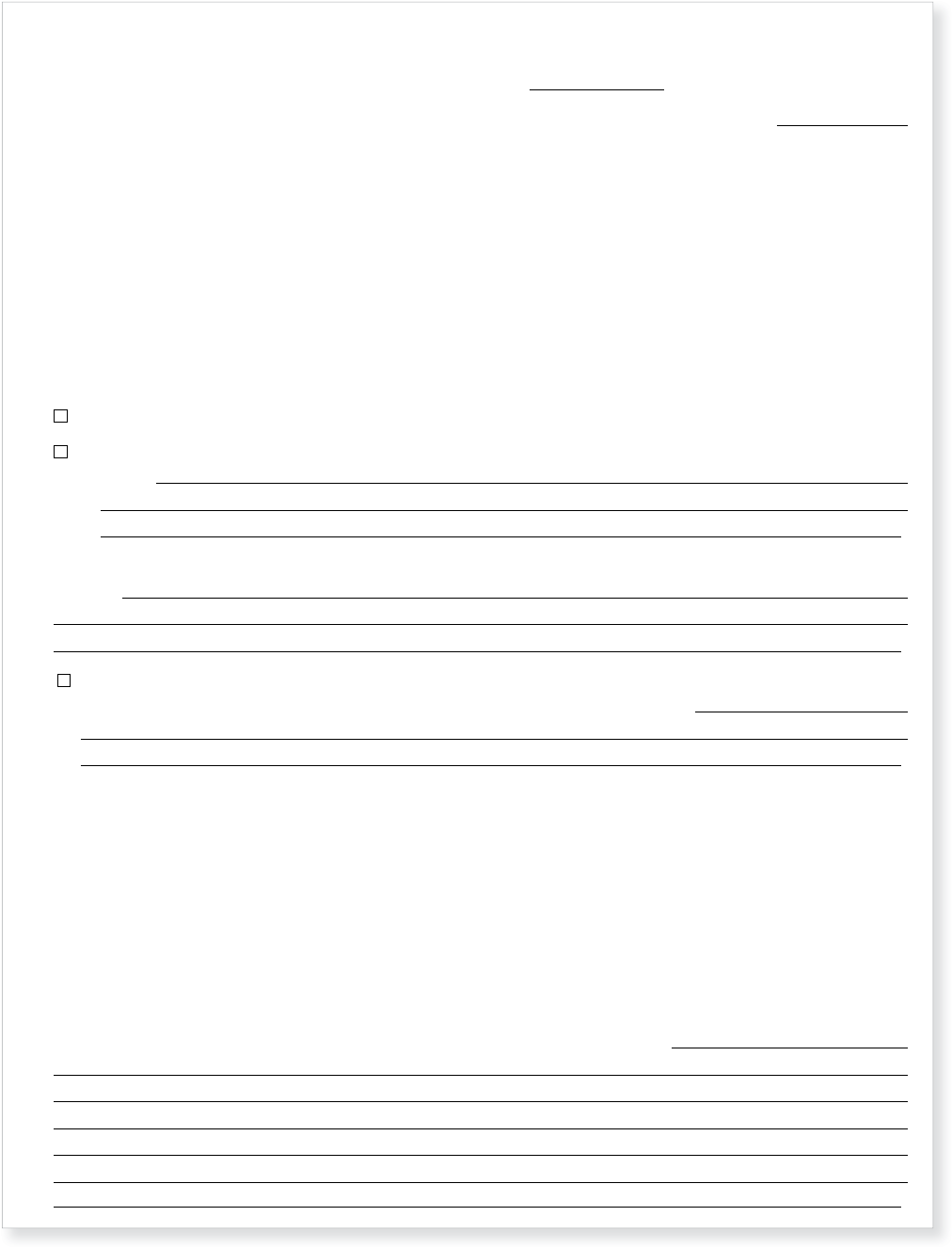

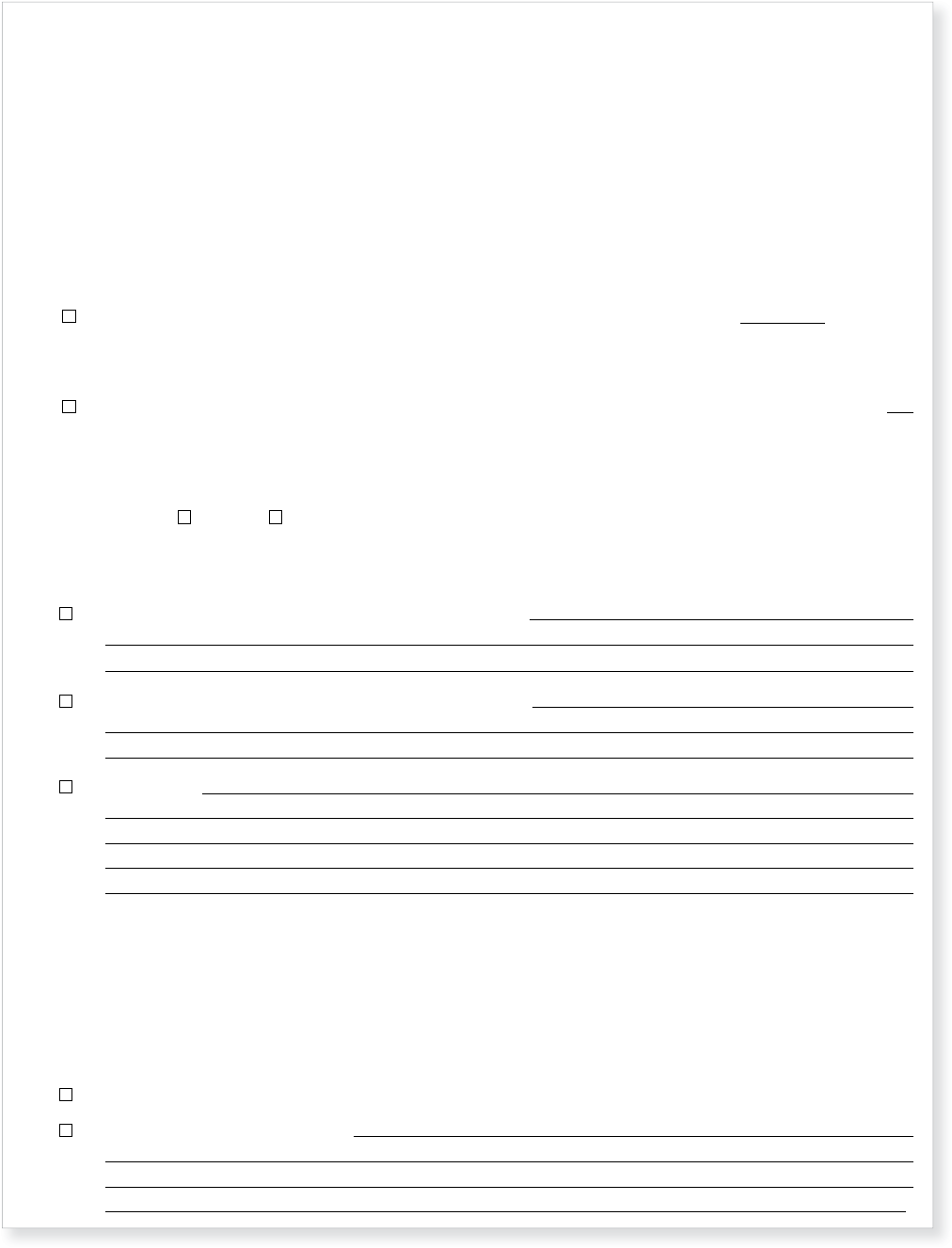

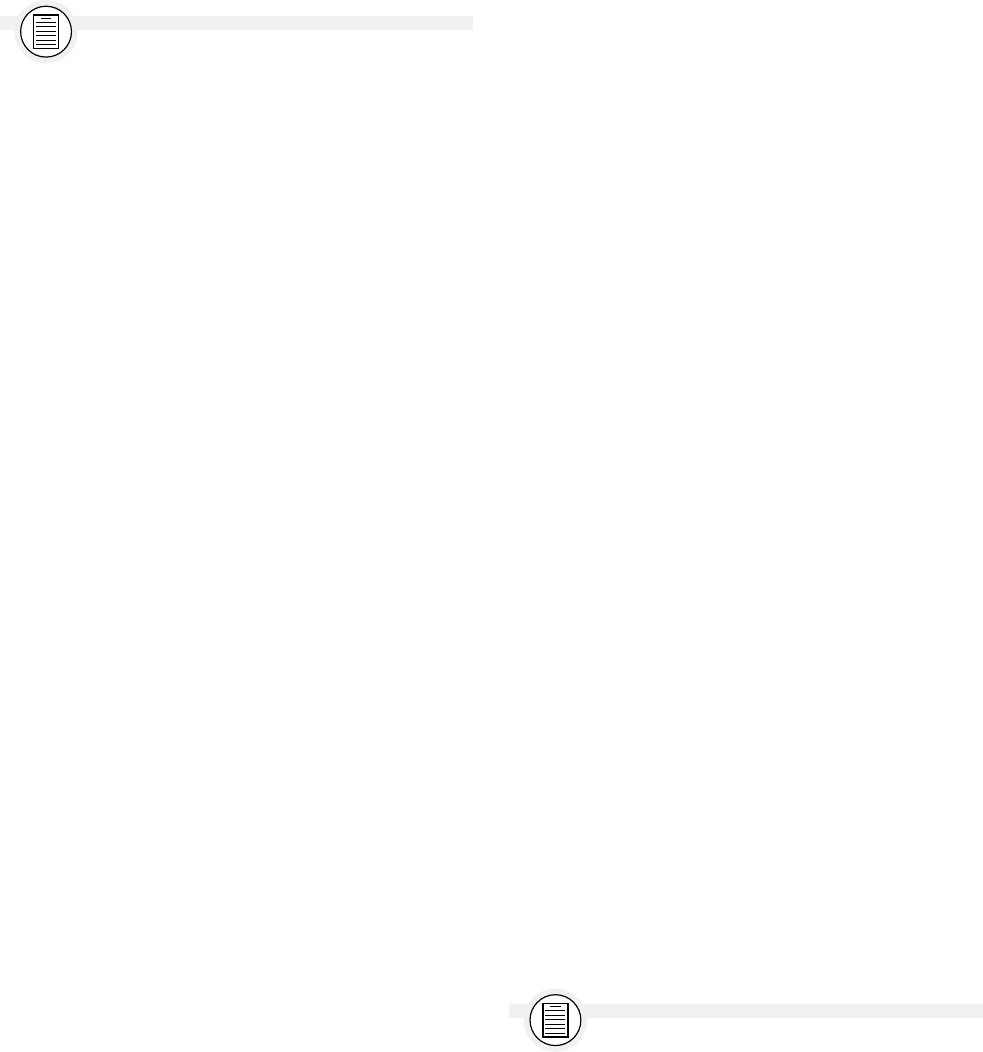

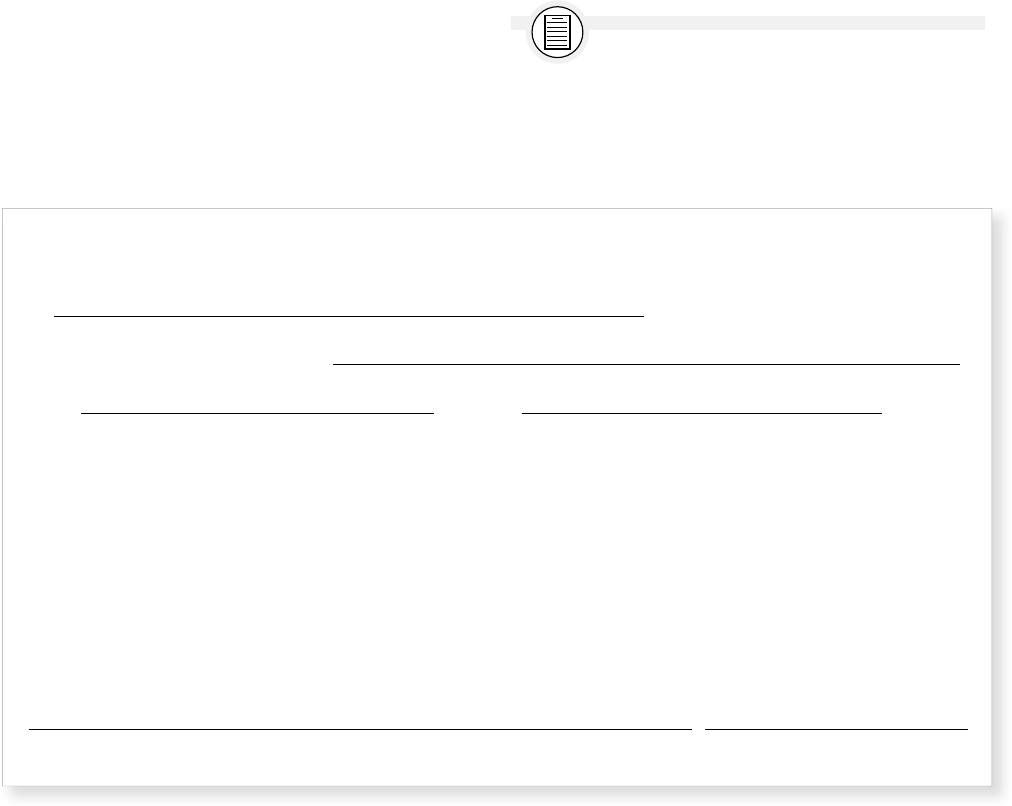

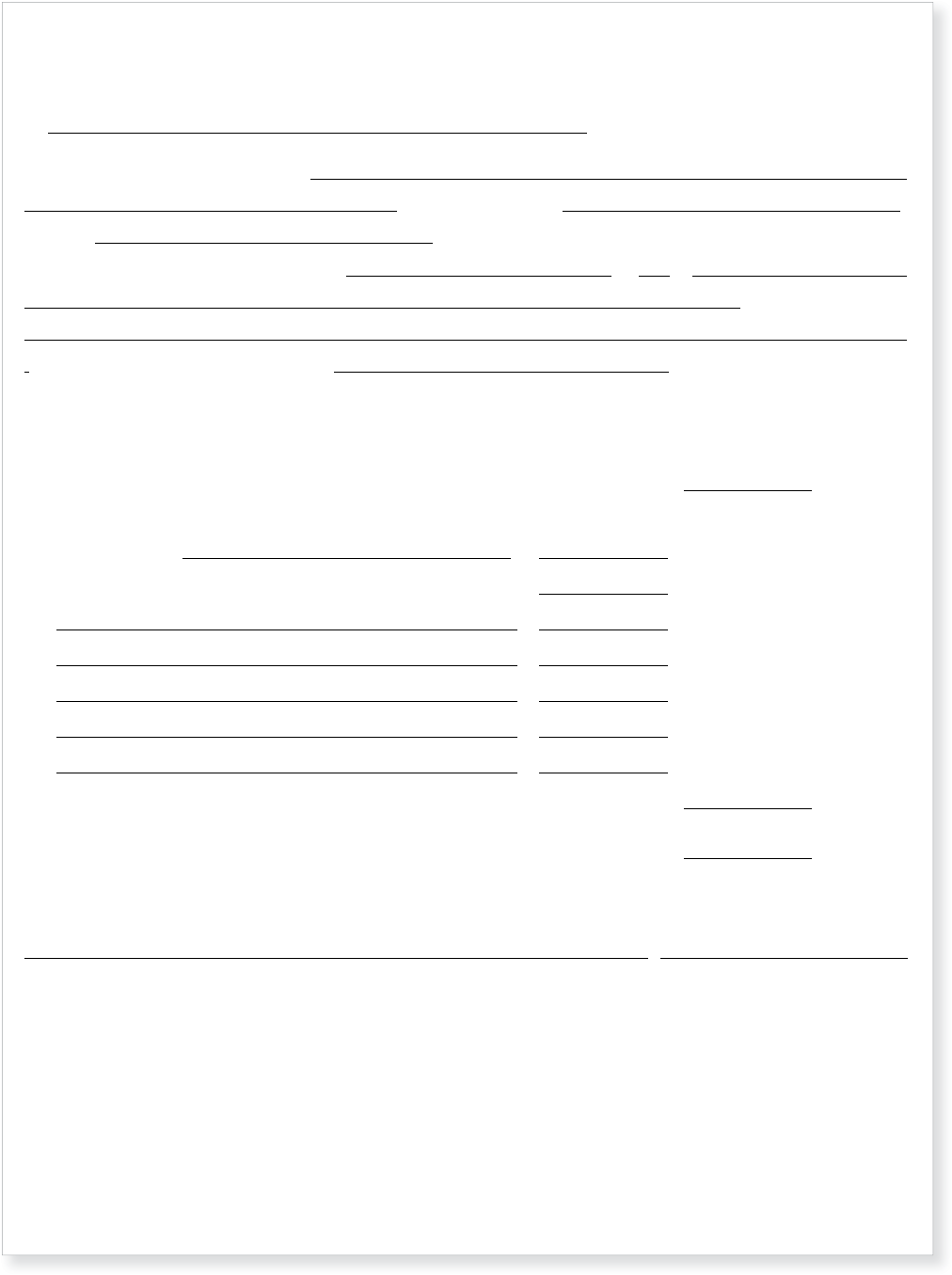

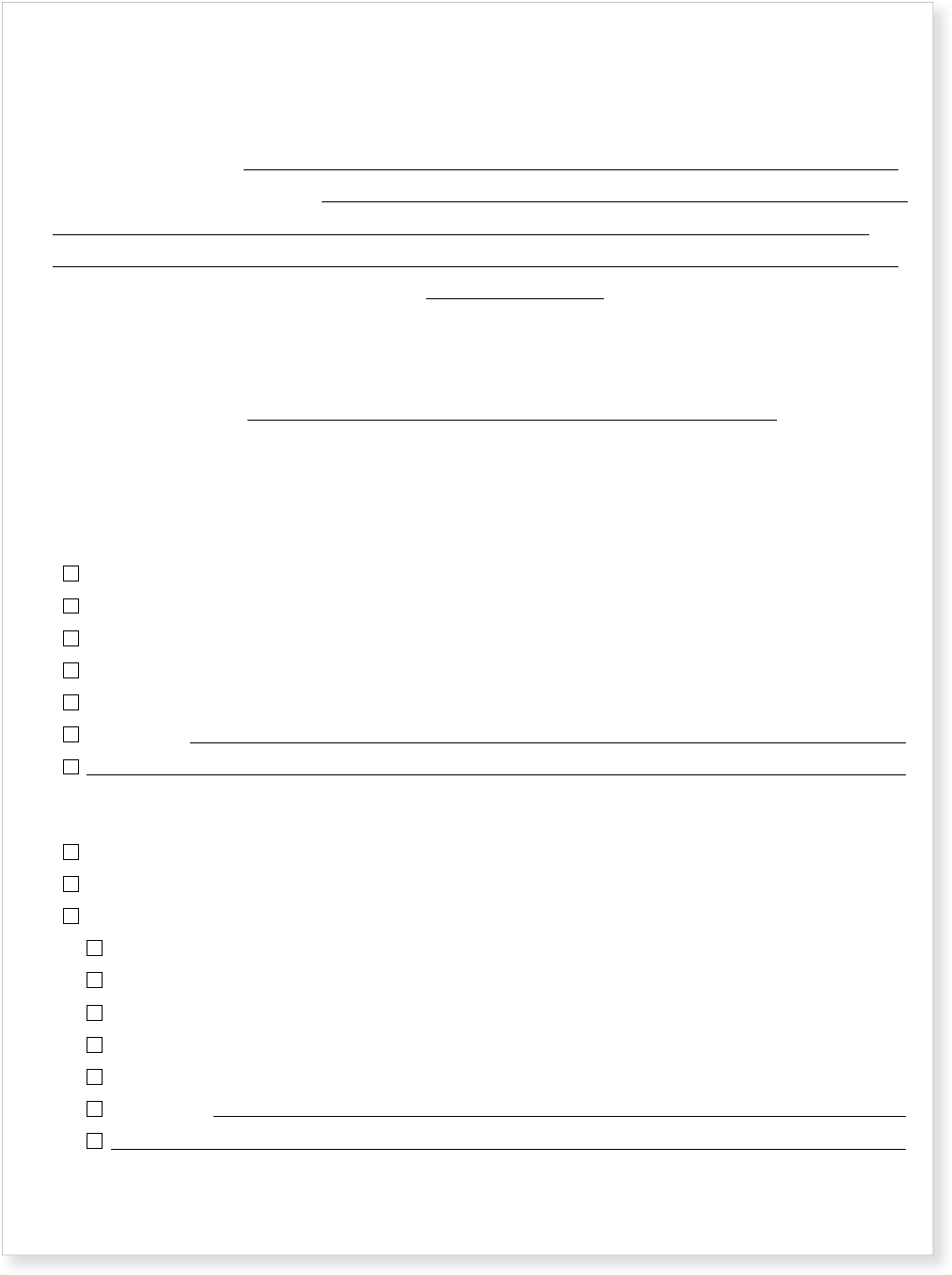

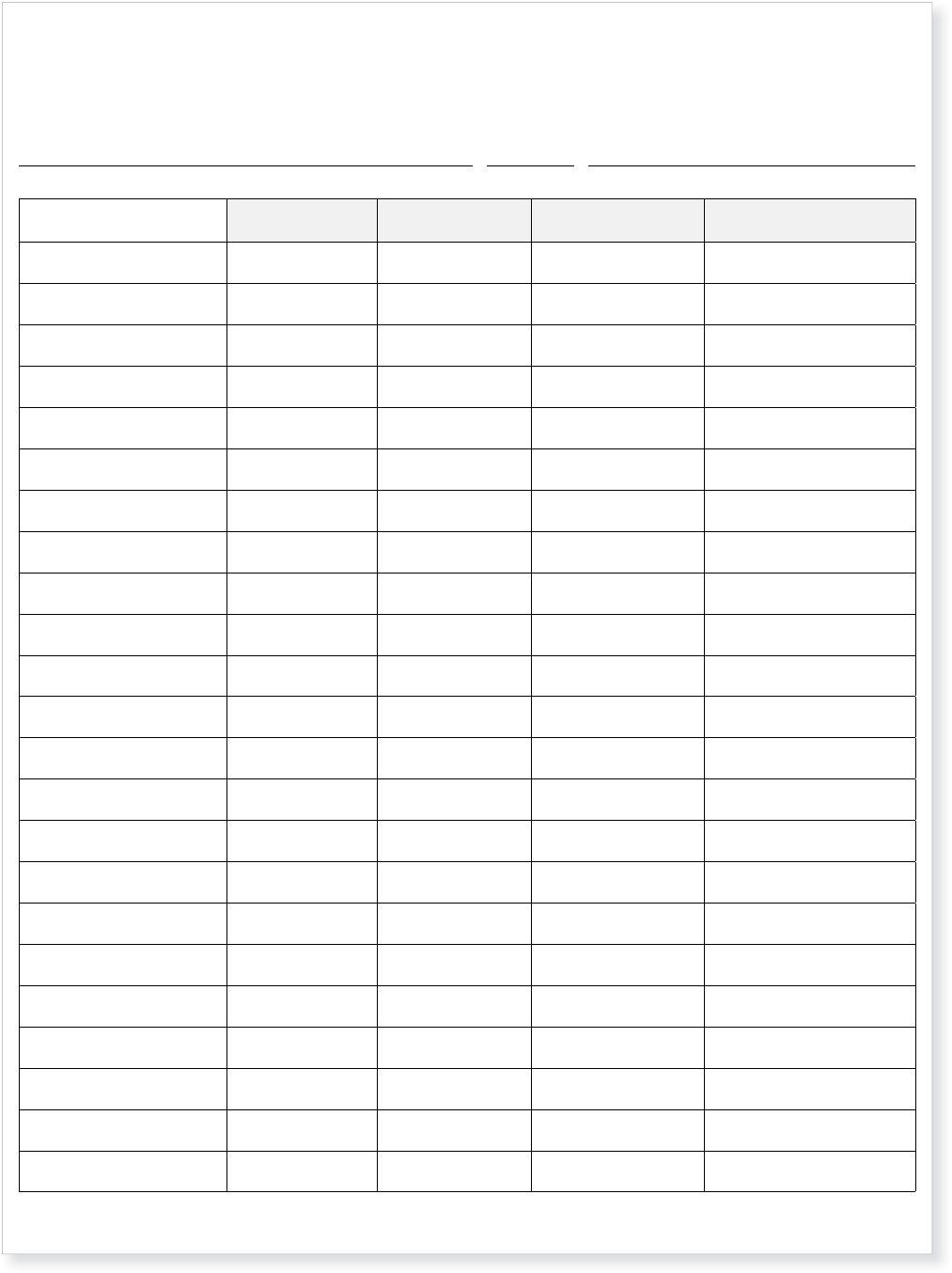

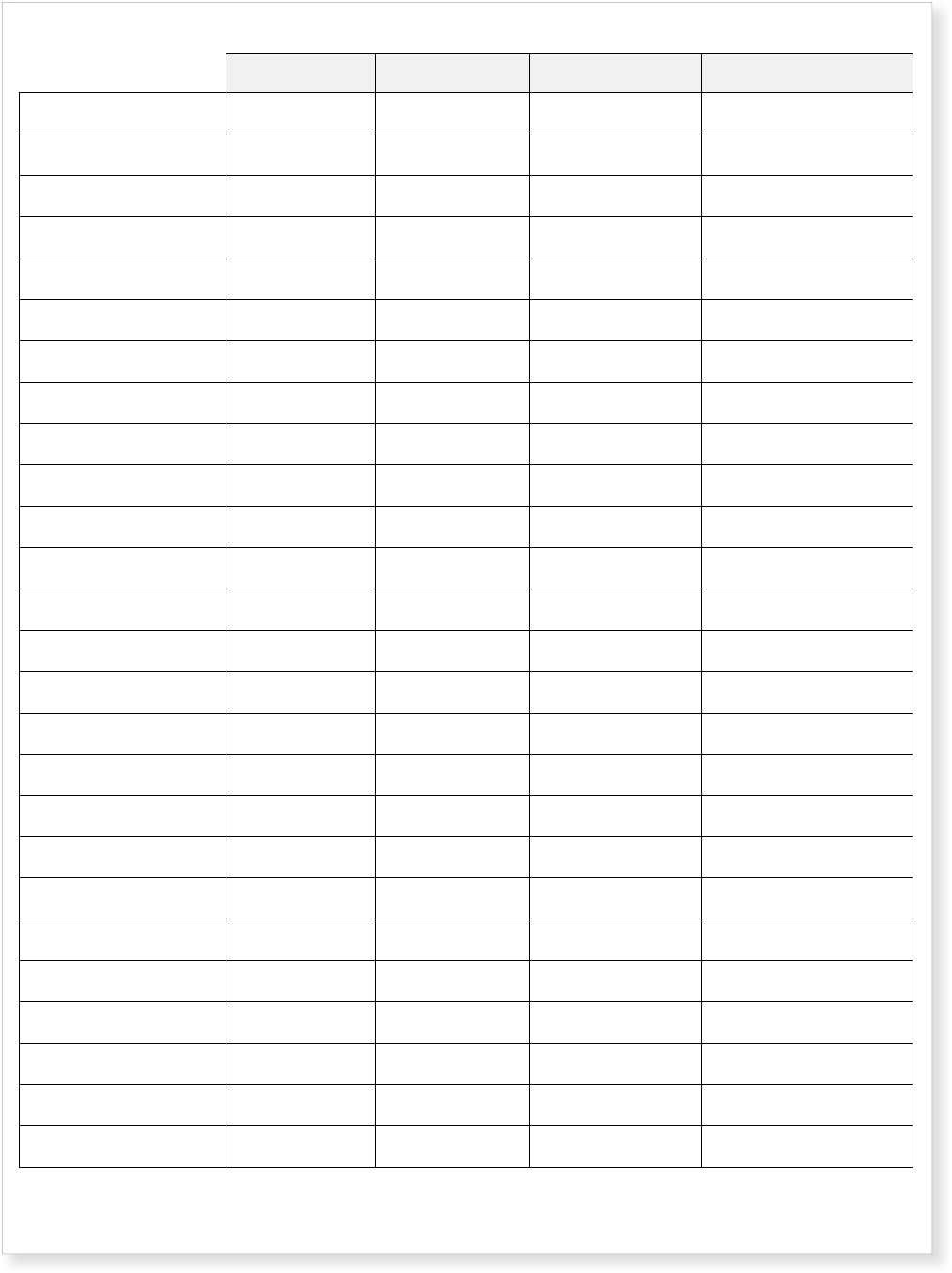

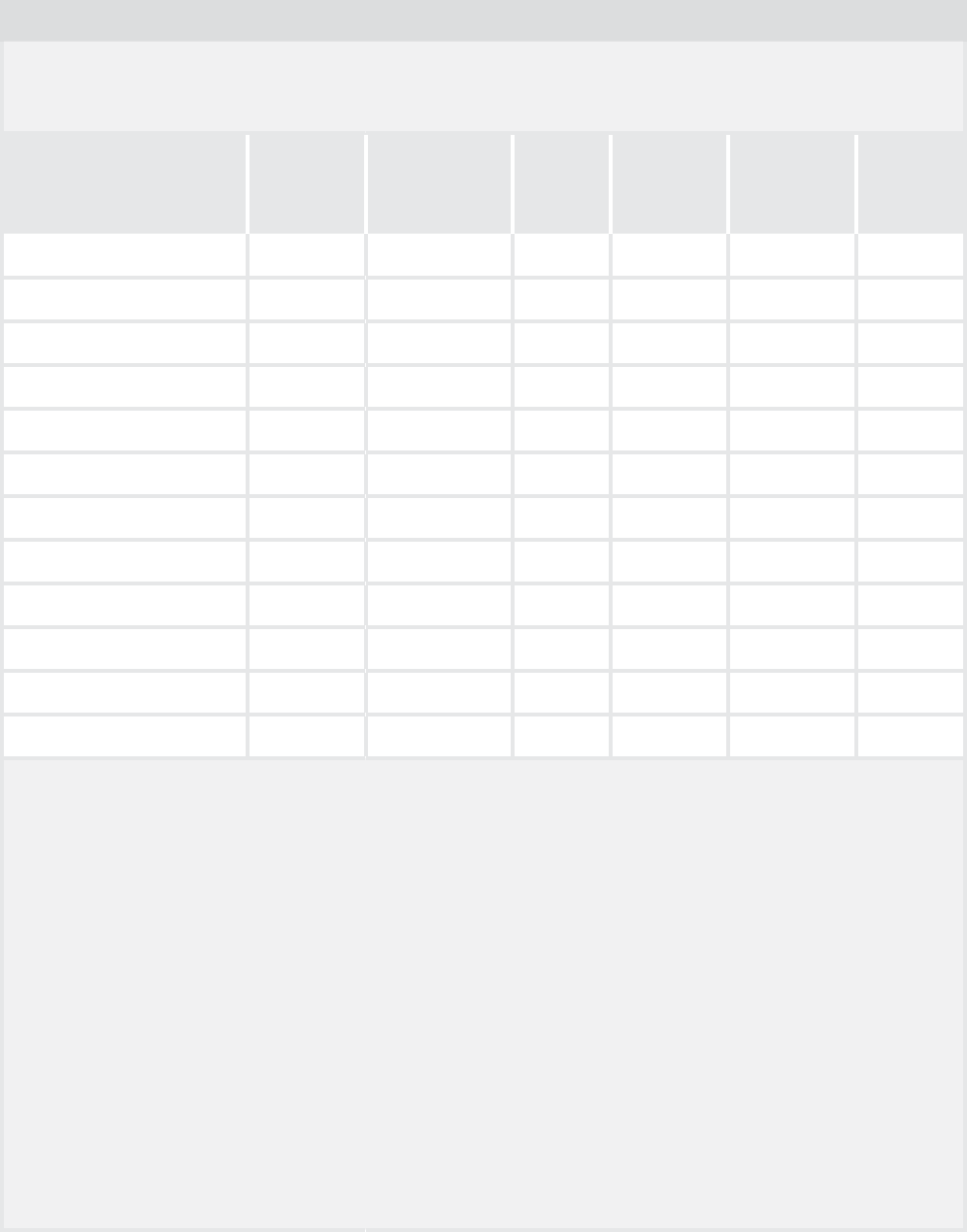

See the sample Rental Application below.

FORM

You’ll find a downloadable copy (both PDF and

RTF versions) of the Rental Application on the Nolo website.

See Appendix B for the link to the forms in this book. You can

use the PDF version (print as is and give it to your applicants)

or the RTF version. You can edit the RTF version and add or

delete questions, but be aware that extensive changes might

affect the form’s layout (the margins and available space for

answers).

Complete the box at the top of the Rental Application,

listing the property address, details on the rental term

and amounts due before the tenants may move in.

Ask all applicants to fill out a Rental Application

form, and accept applications from everyone who’s

interested in your rental property. Refusing to take

an application may unnecessarily anger a prospective

tenant, and will make him or her more likely to look

into the possibility of filing a discrimination complaint.

Make decisions about who will rent the property later.

The Rental Application form includes a section for

you to note the amount and purpose of any credit

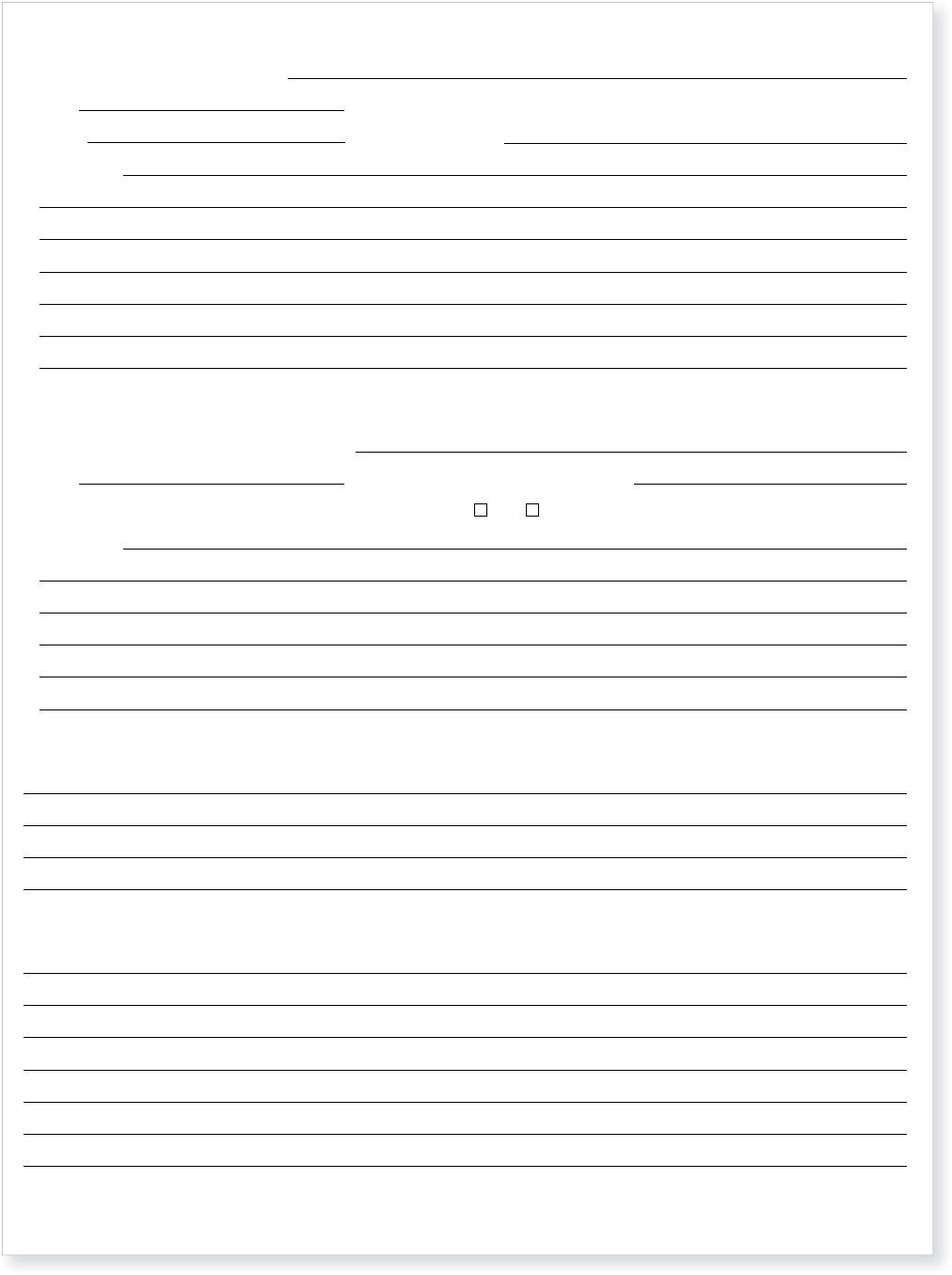

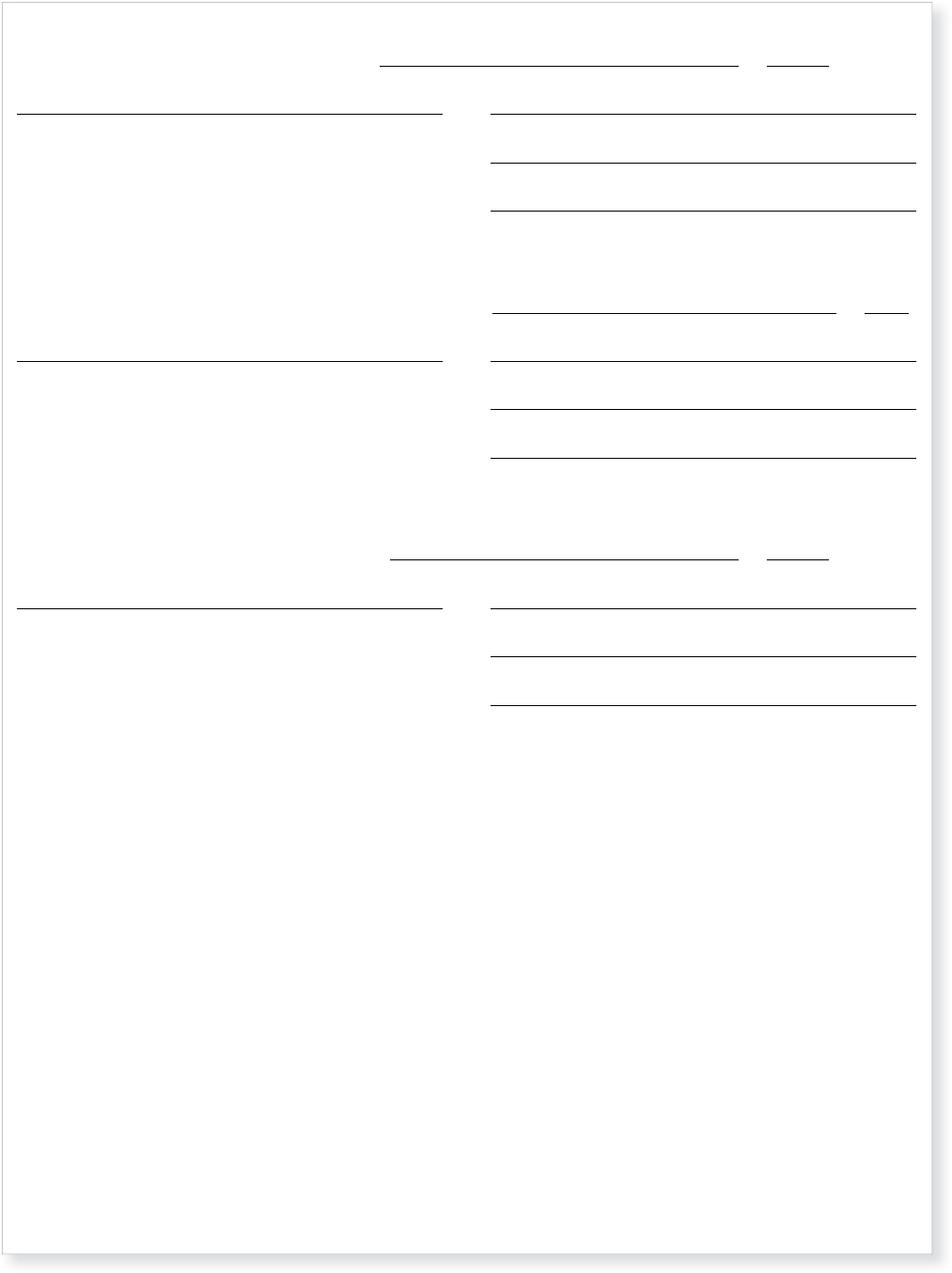

Rental Application

Separate application required from each applicant age 18 or older.

THIS SECTION TO BE COMPLETED BY LANDLORD

Address of Property to Be Rented:

Rental Term: ■ month to month ■ lease from to

Amounts Due Prior to Occupancy

First month’s rent ............................................................................................................................................. $

Security deposit ................................................................................................................................................ $

Credit-check fee ................................................................................................................................................ $

Other (specify): $

TOTAL .......................................................................................................................................................... $

Applicant

Full Name—include all names you use(d):

Home Phone: Work Phone: Cell Phone:

Fax (By providing this number, I agree to receive Fax transmissions from the landlord or landlord’s agent):

Email: Social Security Number:

Driver’s License Number/State:

Other Identifying Information:

Vehicle Make:

Model: Color: Year:

License Plate Number/State:

Additional Occupants

List everyone, including children, who will live with you:

Full Name Relationship to Applicant

Rental History

Current Address:

Dates Lived at Address: Reason for Leaving:

Landlord/Manager: Landlord/Manager’s Phone:

178 West 8th Street, Apt. 6, Oakland, CA

3

March 1, 20xx February 28, 20xx

1,200

1,800

30

3,030

Hannah Silver

510-555-3789 510-555-4567

hannah@coldmail.com 123-000-4567

CA V123456

Toyota Camry White 2008

CA 123456

Dennis Olson Husband

39 Maple Street, Oakland, CA

May 2000 – date Wanted bigger place

Jane Tucker 510-555-7523

8

|

THE CALIFORNIA LANDLORD’S LAW BOOK: RIGHTS & RESPONSIBILITIES

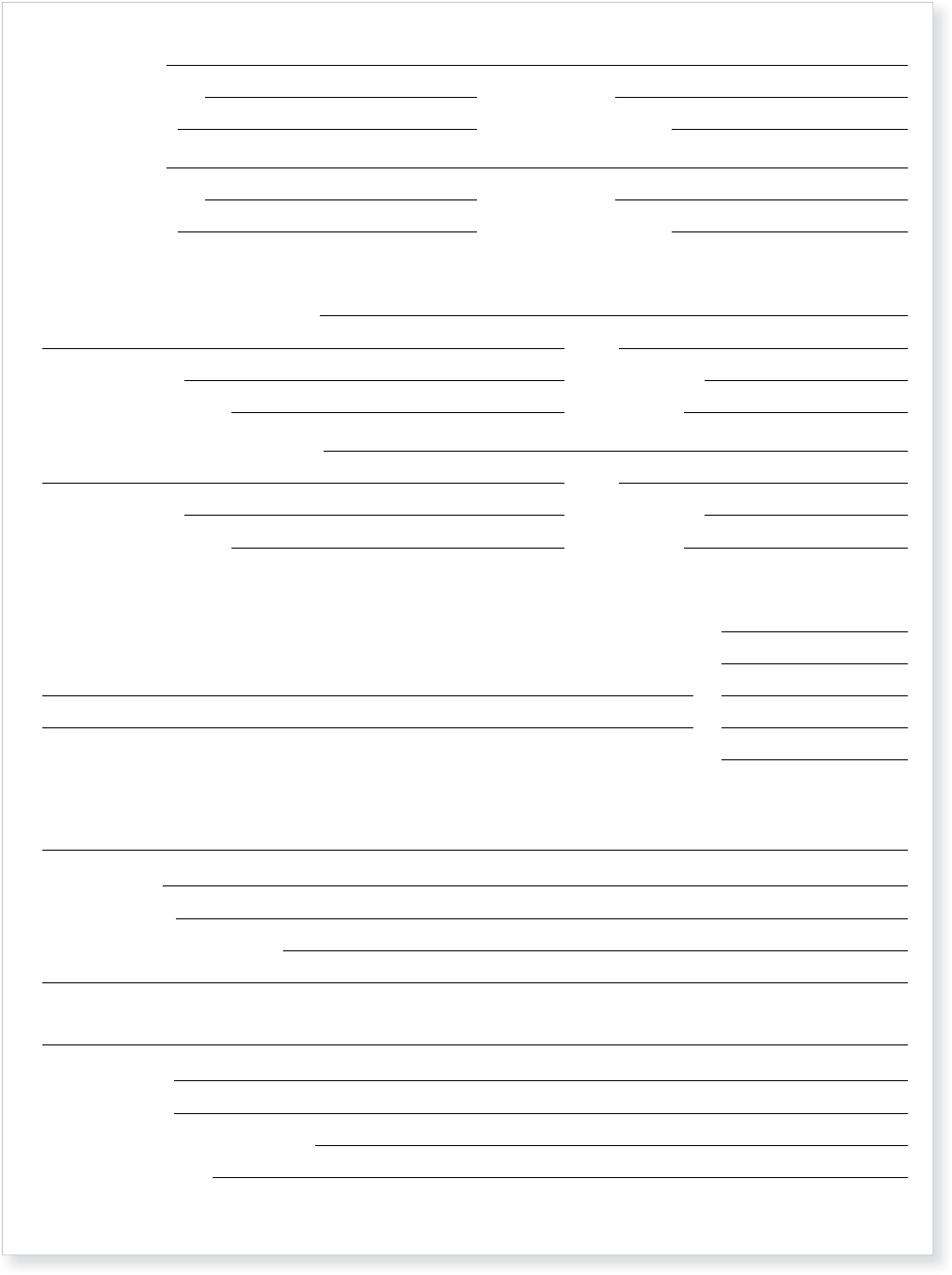

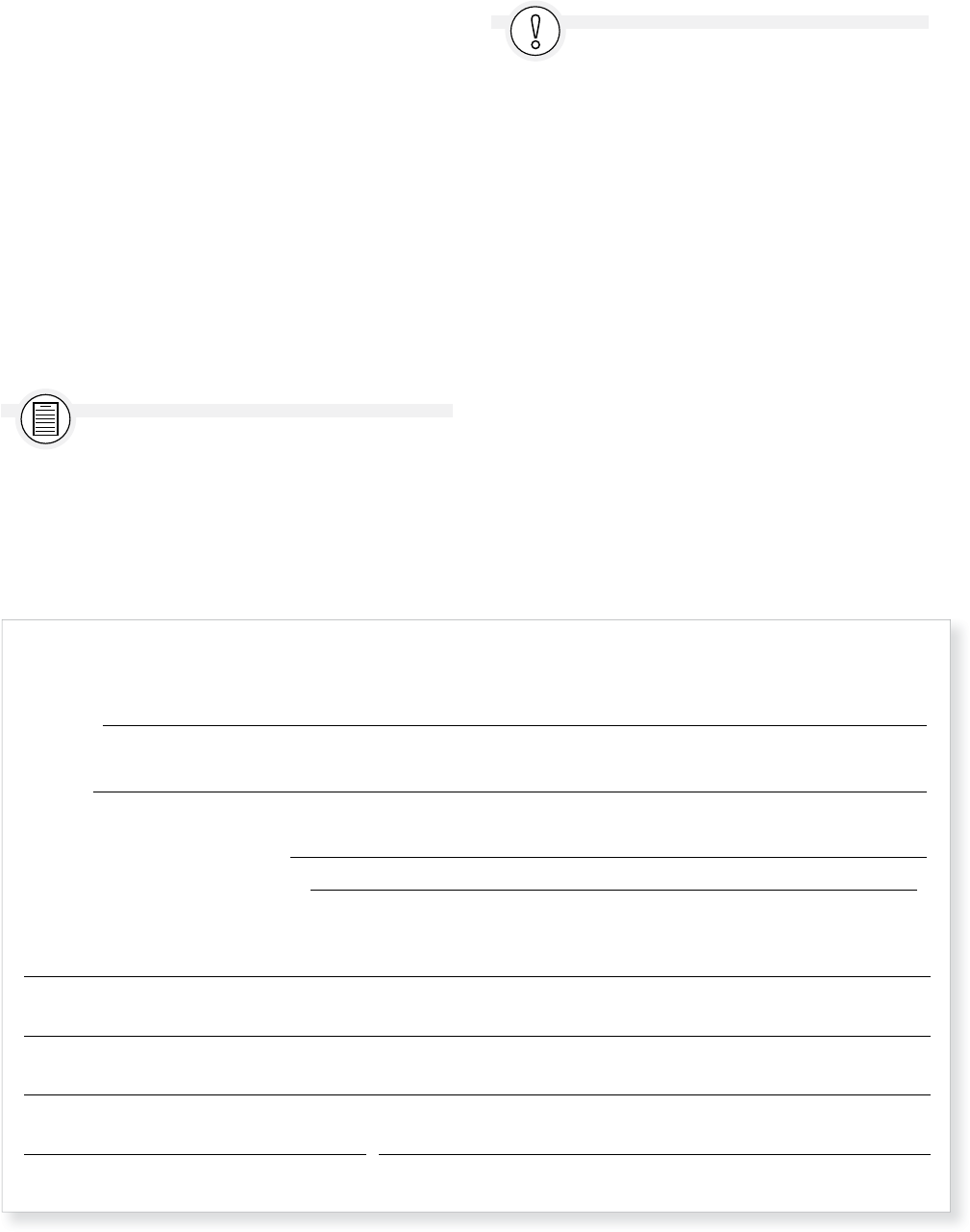

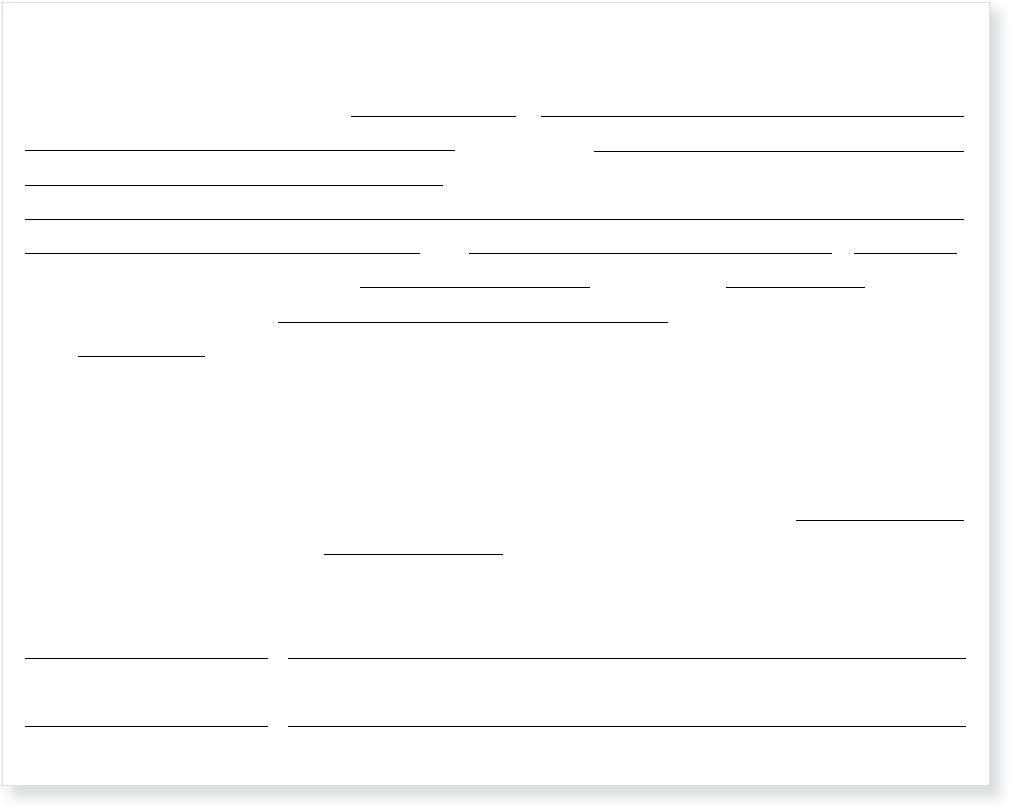

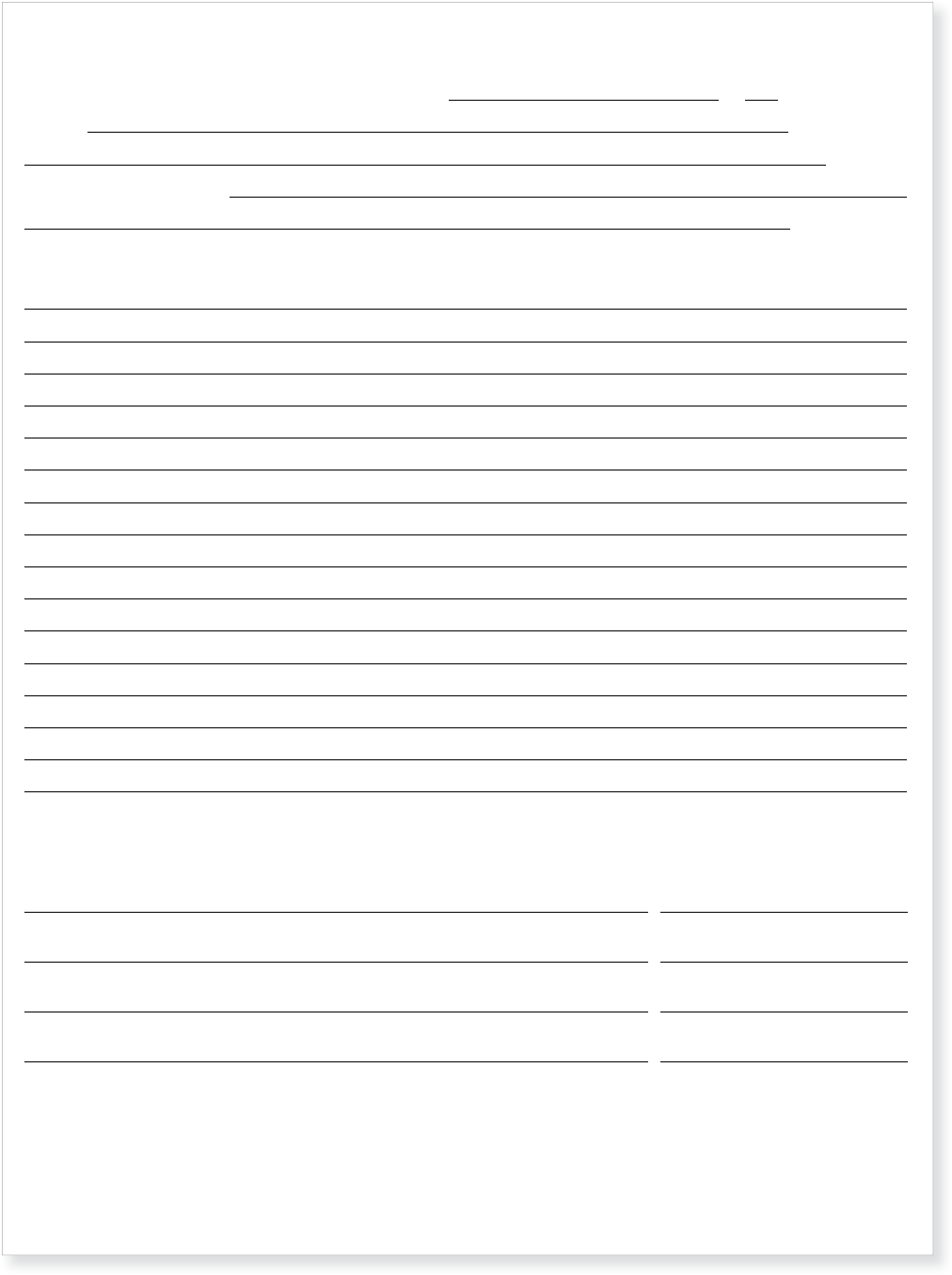

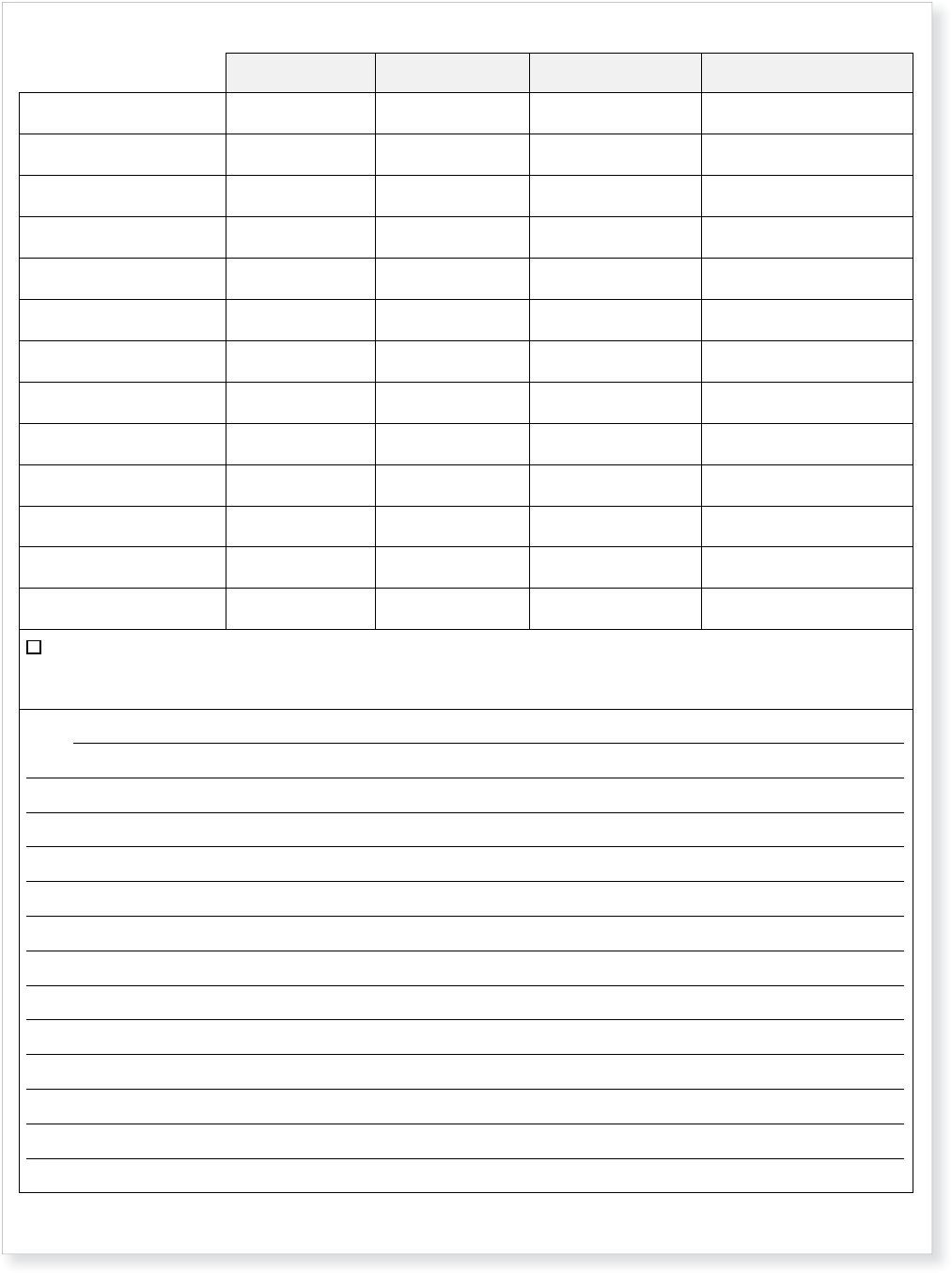

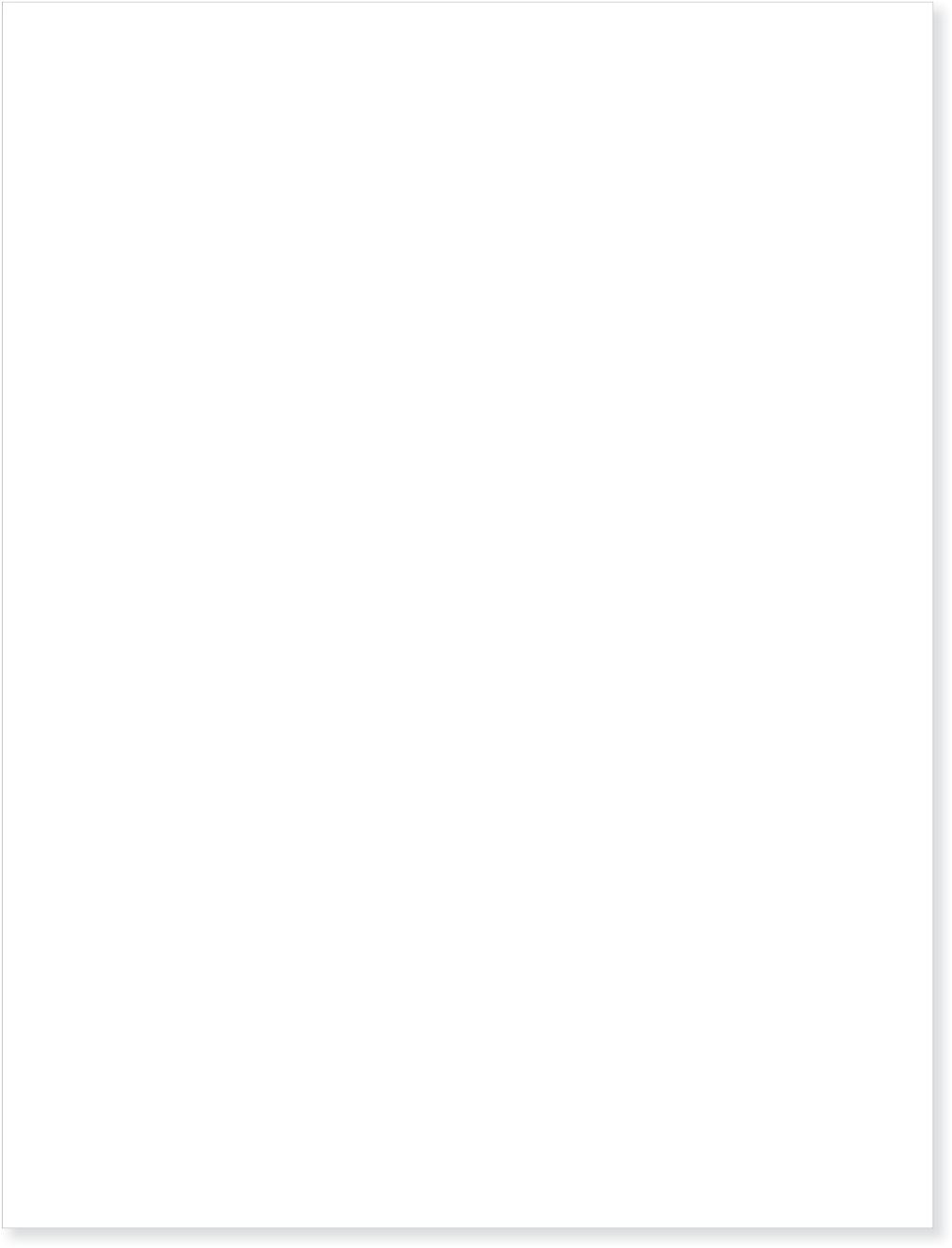

Previous Address:

Dates Lived at Address: Reason for Leaving:

Landlord/Manager: Landlord/Manager’s Phone:

Previous Address:

Dates Lived at Address: Reason for Leaving:

Landlord/Manager: Landlord/Manager’s Phone:

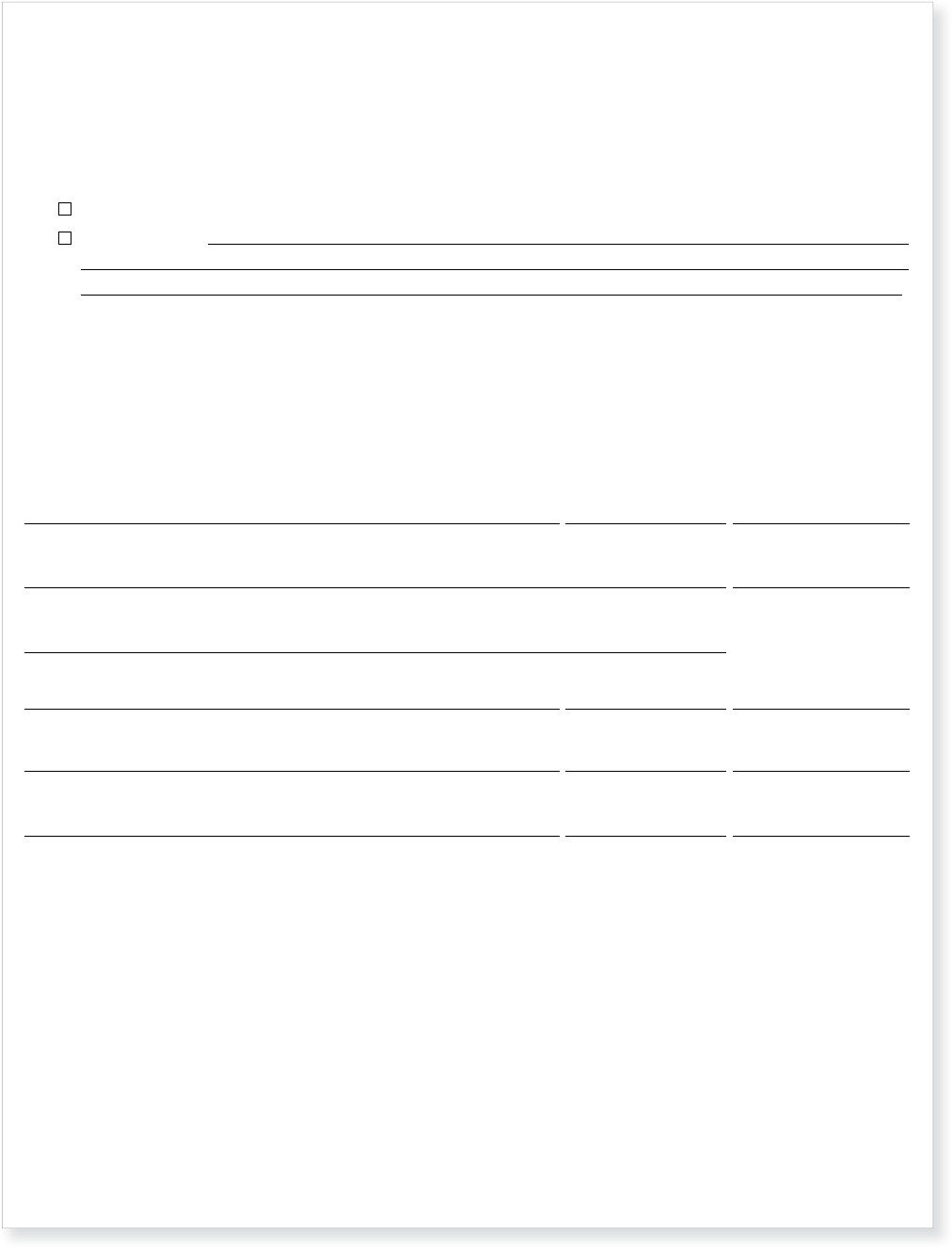

Employment Histor

y

Name and Address of Current Employer:

Phone:

Name of Supervisor: Supervisor’s Phone:

Dates Employed at is Job: Position or Title:

Name and Address of Previous Employer:

Phone:

Name of Supervisor: Supervisor’s Phone:

Dates Employed at is Job: Position or Title:

Income

1. Your gross monthly employment income (before deductions): $

2. Average monthly amounts of other income (specify sources):

$

$

$

TOTAL: $

Cr

edit and Financial Information

Bank/Financial Accounts Account Number Bank/Institution Branch

Savings Account:

Checking Account:

Money Market or Similar Account:

Type of Account Account Name of Amount M

onthly

Credit Accounts & Loans (Auto loan, Visa, etc.) Number Creditor Owed Paymen

t

Major Credit Card:

Major Credit Card:

Loan (mortgage, car, student loan, etc.):

Other Major Obligation:

1215 Middlebrook Road, Palo Alto, CA

June 1997 – May 2000 New job in East Bay

Ed Palermo 650-555-3711

152 Highland Drive, Santa Cruz, CA

Jan. 1996 – June 1997 Wanted to live closer to work

Millie & Joe Lewis 831-555-9999

Argon Works, 54 Nassau Road, Berkeley, CA

510-555-2333

Tom Schmidt 510-555-2333

2000 – date Marketing Director

Palo Alto Tribune

13 Junction Road, Palo Alto 650-555-2366

Do r y K r o ss b e r 65 0 -555 -1111

1996 –2000 Marketing Associate

5,000

husband’s salary 4,000

9,000

1222345 Cal West Berkeley, CA

789101 Cal West Berkeley, CA

234789 City Bank San Francisco, CA

Visa 123456 City Bank $1,000 $500

Dept. Store 45789 Macy’s $500 $500

ChApter 1 |RENTING YOUR PROPERTY

|

9

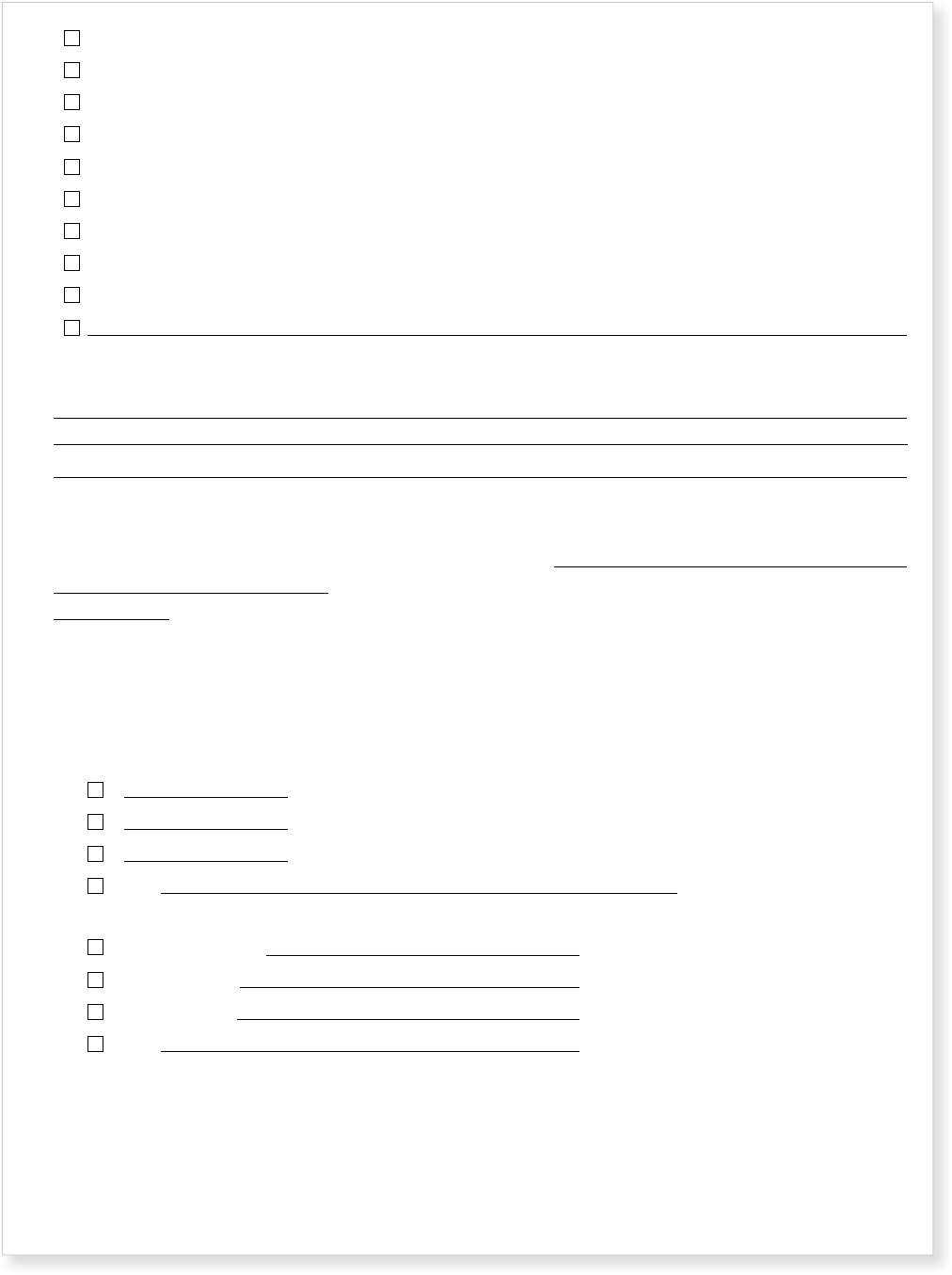

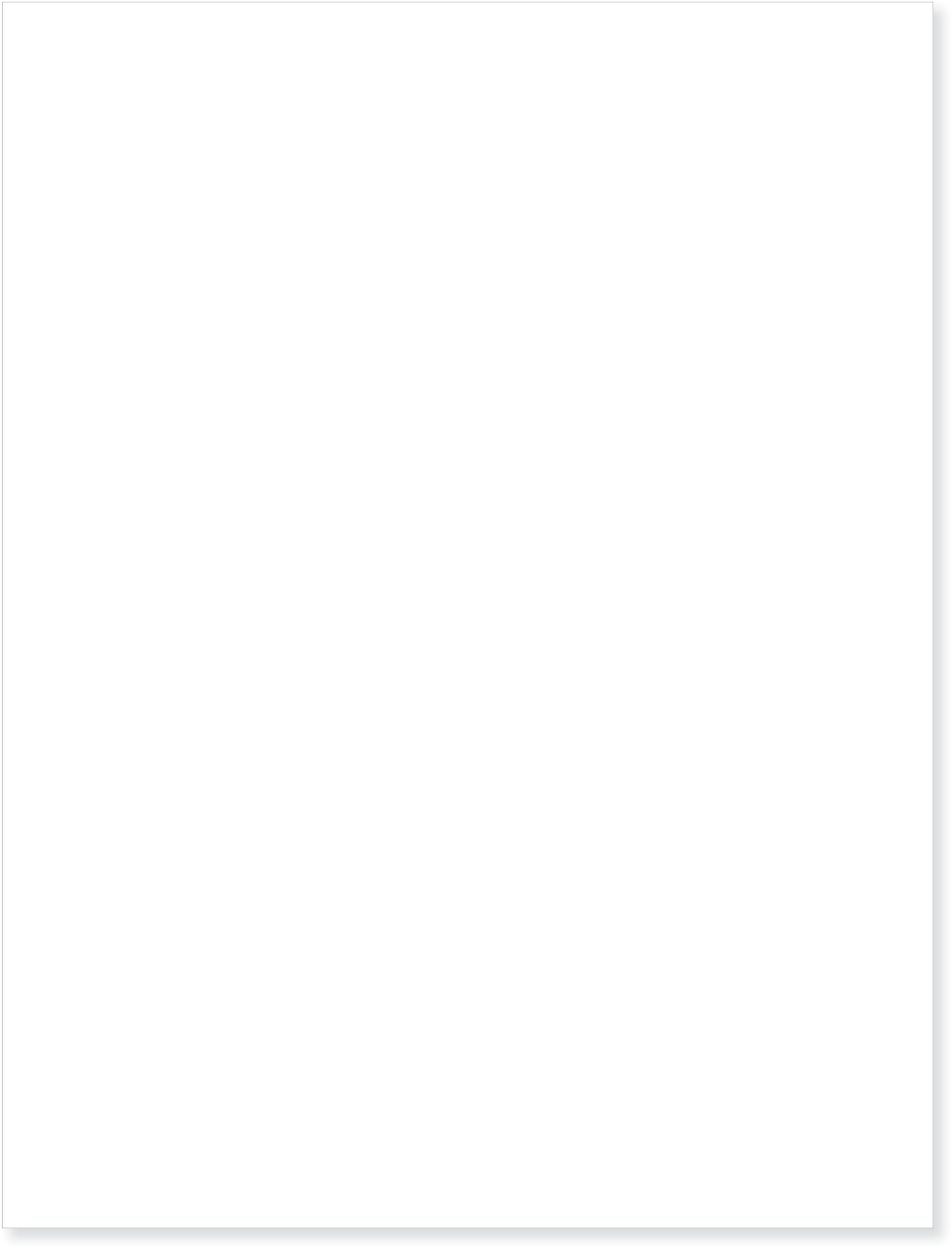

Miscellaneous

Describe the number and type of pets you want to have in the rental property:

Describe water-fi lled furniture you want to have in the rental property:

Do you smoke? ■ yes ■ no

Have you ever: Filed for bankruptcy? ■ yes ■ no Been sued? ■ yes ■ no

Been evicted? ■ yes ■ no Been convicted of a crime? ■ yes ■ no

Explain any “yes” listed above:

References and Emergency Contact

Personal Reference: Relationship:

Address:

Phone:

Personal Reference: Relationship:

Address:

Phone:

Contact in Emergency: Relationship:

Address:

Phone:

I certify that all the information given above is true and correct and understand that my lease or rental agreement may be

terminated if I have made any material false or incomplete statements in this application. I authorize verifi cation of the information

provided in this application from my credit sources, credit bureaus, current and previous landlords and employers, and personal

references. I understand that if I have initiated a “security freeze” on my credit information with any of the credit reporting

agencies, I will promptly lift the freeze for a reasonable time so that my credit report may be accessed by the Landlord/Manager;

and I understand that if I fail to do so, the Landlord/Manager may consider this an incomplete application. (CC § 1785.11.2.) is

permission will survive the expiration of my tenancy.

Date

Applicant

Notes (Landlord/Manager):

No pets

None

X

X X

X X

Joan Stanley friend, co-worker

785 Spruce Street, Berkeley

510-555-4578

Marnie Swatt friend

785 Pierce Avenue, San Francisco

415-555-7878

Connie and Martin Silver Parents

123 Gorham Street, Princeton, N.J.

609-555-8765

Feb. 15, 20xx Hn Svr

10

|

THE CALIFORNIA LANDLORD’S LAW BOOK: RIGHTS & RESPONSIBILITIES

ChApter 1 |RENTING YOUR PROPERTY

|

11

check fee. (Credit check fees are discussed below.)

If you do not charge credit check fees, simply fill in

“none” or “N/A.”

Be sure all potential tenants sign the Rental

Application, authorizing you to verify the information

and references. (Some employers and others require

written authorization before they will talk to you.) You

may also want to prepare a separate authorization,

so that you don’t need to copy the entire application

and send it off every time a bank or employer wants

proof that the tenant authorized you to verify the

information. See the sample Consent to Background

and Reference Check, below.

FORM

You’ll fi nd a downloadable copy of the Consent

to Background and Reference Check on the Nolo website.

See Appendix B for the link to the forms in this book.

CAUTION

Don’t take incomplete rental applications.

Landlords are often faced with anxious, sometimes

desperate people who need a place to live immediately.

Some people tell terrifi c hard-luck stories as to why normal

credit- and reference-checking rules should be ignored in

their case and why they should be allowed to move right in.

Don’t believe any of it. People who have planned so poorly

that they will literally have to sleep in the street if they

don’t rent your place that day are likely to come up with

similar emergencies when it comes time to pay the rent.

Always make sure that prospective tenants complete the

entire Rental Application, including Social Security number

(or an alternative; see below), driver’s license number or

other identifying information (such as a passport number),

current employment, and emergency contacts. You may

need this information later to track down a tenant who

skips town leaving unpaid rent or abandoned property. (See

Chapters 19 and 21.)

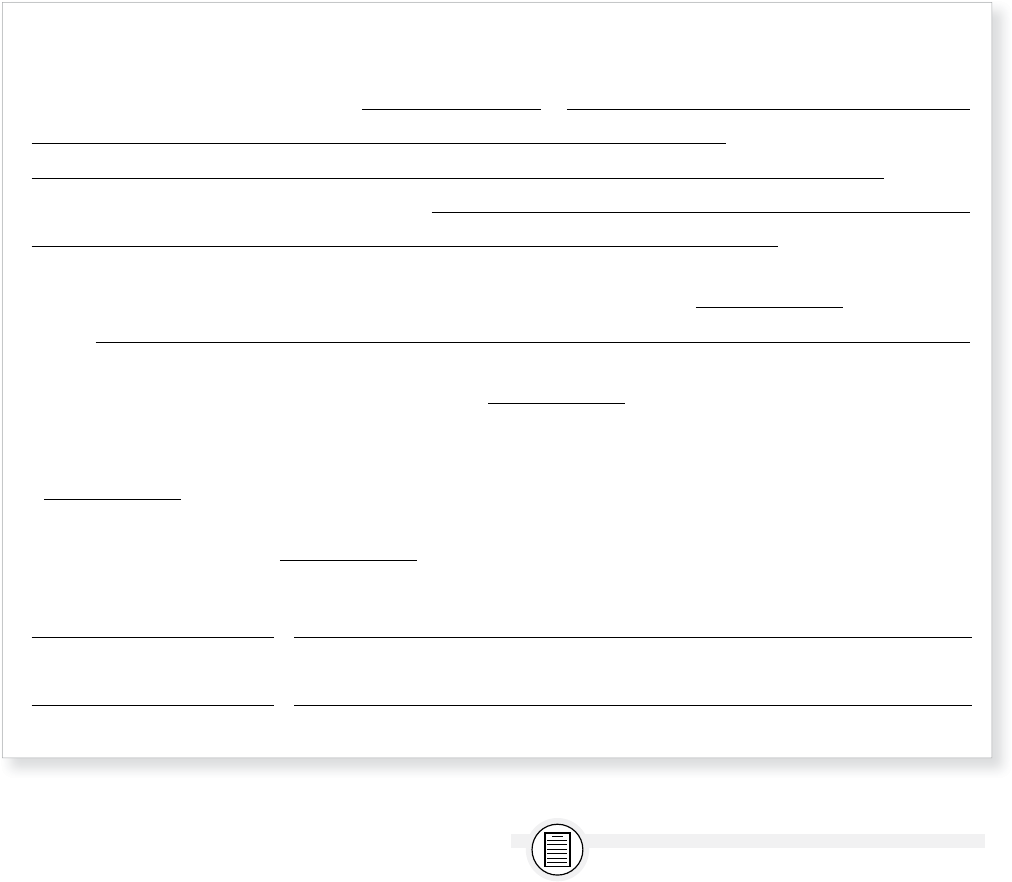

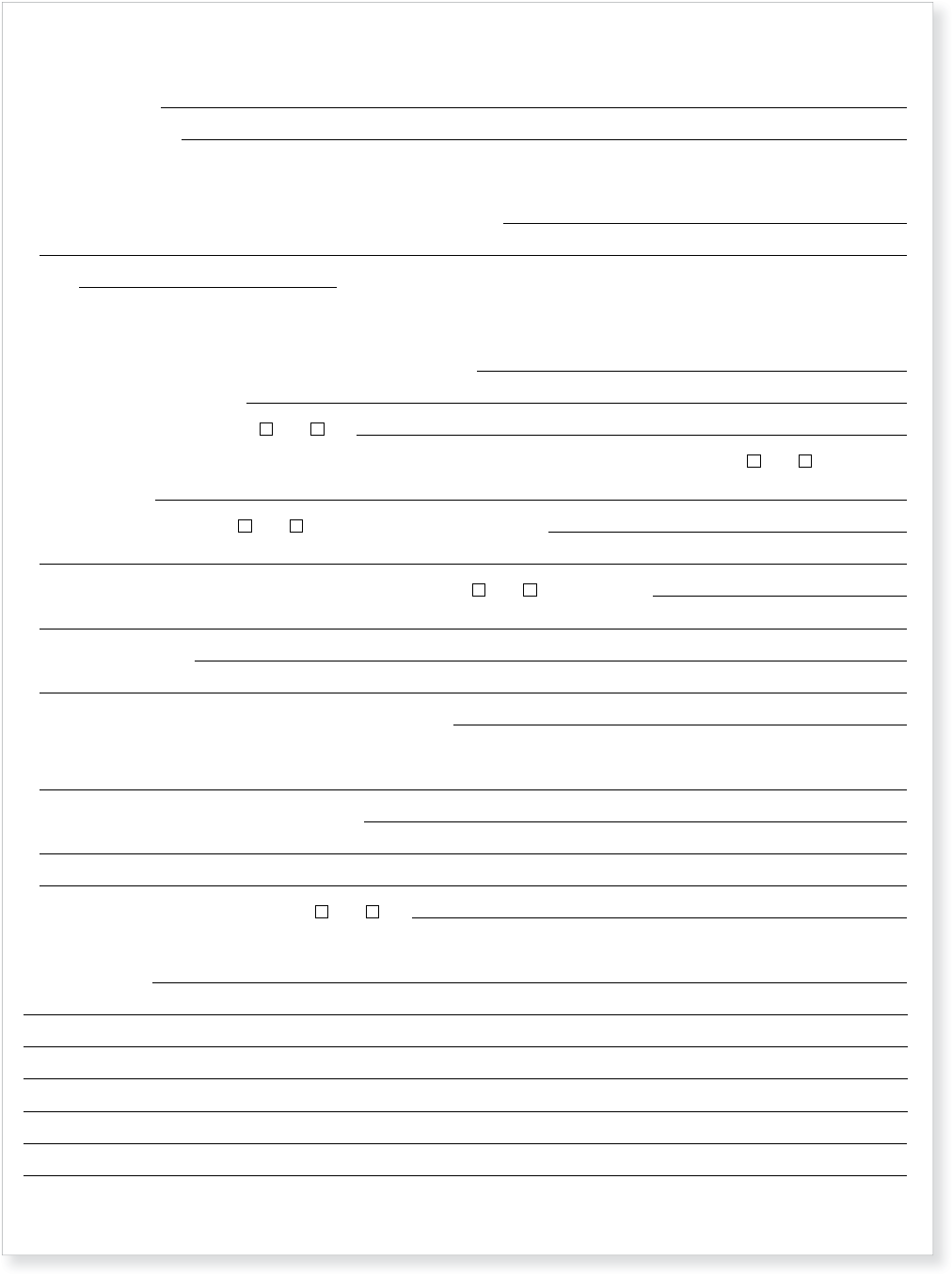

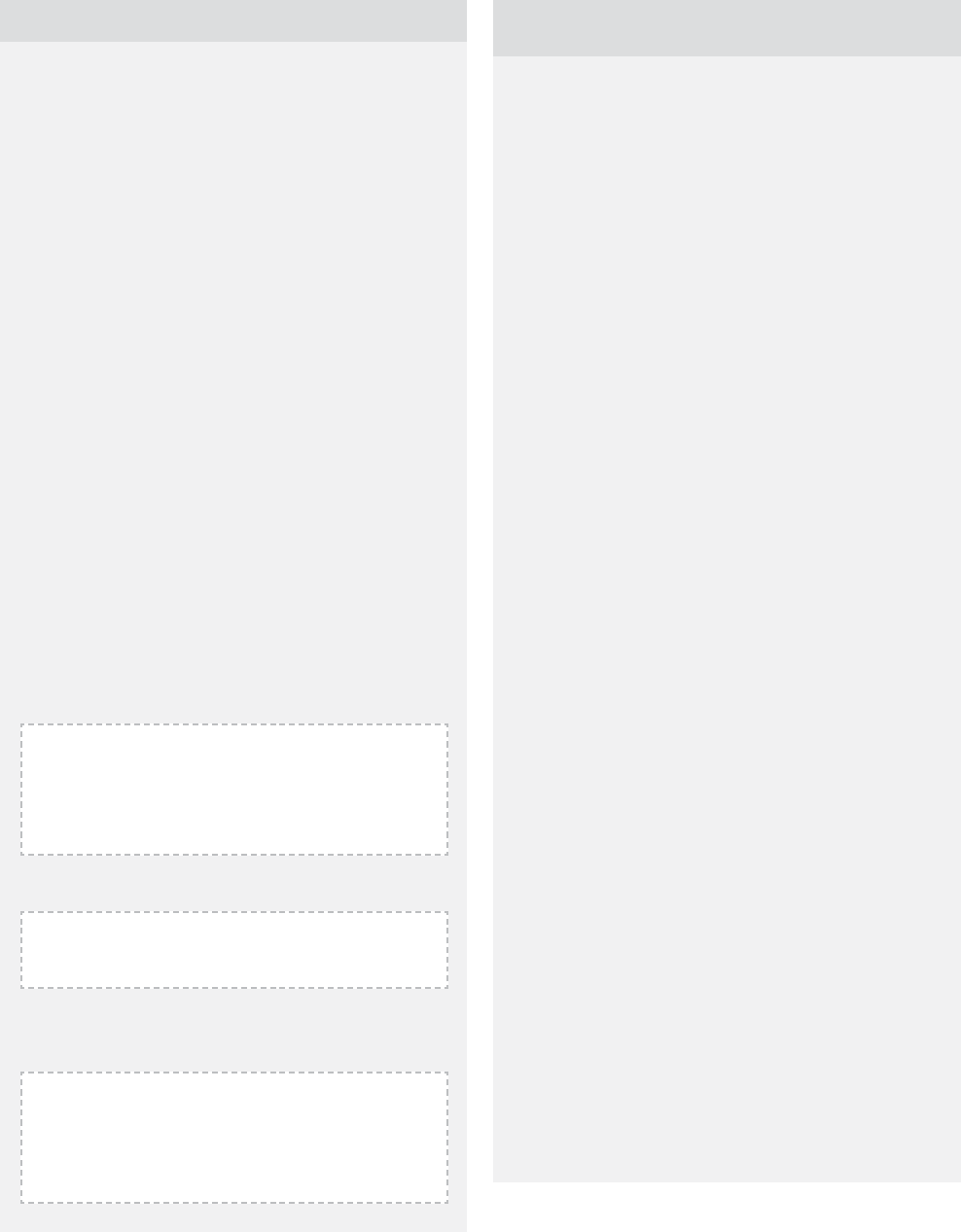

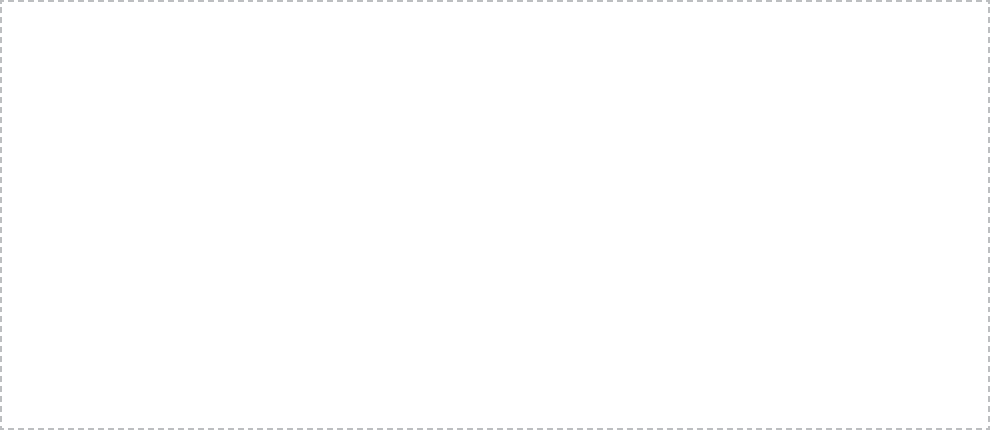

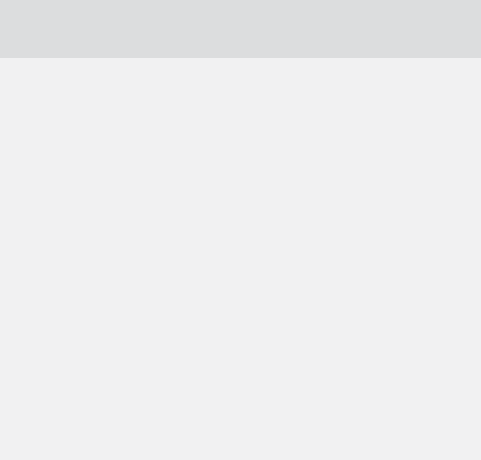

Consent to Background and Reference Check

I authorize

to obtain information about me from my credit sources, current and previous landlords and employers, and personal references,

to enable

to evaluate my rental application. I authorize my credit sources, credit bureaus, current and previous landlords and employers,

and personal references to disclose to

information about me that is relevant to ’s

decisions regarding my application and tenancy. is permission will survive the expiration of my tenancy.

Name

Address

Phone Number

Date Applicant

Jan Gold

Jan Gold

Jan Gold

Jan Gold

Sandy Meyer

4 Elm Road, Sacramento, CA

916-555-9876

May 2, 20xx Sndy Mer

12

|

THE CALIFORNIA LANDLORD’S LAW BOOK: RIGHTS & RESPONSIBILITIES

An Alternative to Requiring

Social Security Numbers

You may encounter an applicant who does not have an

SSN (only citizens or immigrants authorized to work

in the United States can obtain one). For example,

someone with a student visa will not normally have an

SSN. If you categorically refuse to rent to applicants

without SSNs, and these applicants happen to be foreign

students, you’re courting a fair housing complaint.

Fortunately, nonimmigrant aliens (such as people

lawfully in the United States who don’t intend to stay

here permanently, and even those who are here illegally)

can obtain an alternate piece of identification that will

suit your needs as well as an SSN. It’s called an Individual

Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN), and is issued by

the IRS to people who expect to pay taxes. Most people

who are here long enough to apply for an apartment will

also be earning income while in the United States. and

will therefore have an ITIN. Consumer reporting agencies

and tenant screening companies can use an ITIN to

find the information they need to effectively screen an

applicant. On the Rental Application, use the line “Other

Identifying Information” for an applicant’s ITIN.

Credit Check and Screening Fees

State law limits credit check or application fees you

can charge prospective tenants, and specifies what

you must do when accepting these types of screening

fees. (CC § 1950.6.) You can charge only “actual out-

of-pocket costs” of obtaining a credit or similar tenant

“screening” report, plus “the reasonable value of time

spent” by you or your manager in obtaining a credit

report or checking personal references and background

information on a prospective tenant. We cover credit

reports and other screening efforts below.

To determine the maximum screening fee you can

charge each applicant, go to the Consumer Price Index

website at www.bls.gov/cpi and search for the article,

“How to Use the Consumer Price Index for Escalation,”

which refers you to a calculator. (As of 2013, you can

charge a screening fee up to $42.)

Upon an applicant’s request, you must provide a

copy of any consumer credit report you obtained on

the individual. You must also give or mail the applicant

a receipt itemizing your credit check and screening

fees. If you end up spending less (for the credit report

and your time) than the fee you charged the applicant,

you must refund the difference. (This may be the

entire screening fee if you never get a credit report or

check references on an applicant.)

Finally, you cannot charge any screening or credit

check fee if you don’t have a vacancy and are simply

putting someone on a waiting list (unless the applicant

agrees to this in writing).

In light of state limits on credit check fees, we

recommend that you:

•charge a credit check fee only if you intend to

actually obtain a credit report

•charge only your actual cost of obtaining the

report, plus $10, at most, for your time and trouble

•charge no more than $42 per applicant in any

case (unless you include an adjustment based on

the CPI)

•provide an itemized receipt at the same time you

take an individual’s rental application (a sample

receipt is shown below), and

•mail each applicant a copy of his or her credit

report as a matter of practice.

FORM

You’ll find a downloadable copy of the

Application Screening Fee Receipt on the Nolo website. See

Appendix B for the link to the forms in this book.

CAUTION

Nonrefundable move-in fees are illegal. Any

“payment, fee, deposit, or charge” that is intended to be

used to cover unpaid rent or damage or that is intended to

compensate a landlord for costs associated with move-in, is

legally considered a security deposit and is covered by state

deposit laws. Security deposits are always refundable. (Chapter

5 covers security deposits.)

Terms of the Rental

Be sure your prospective tenant knows all your general

requirements and any special rules and regulations

before you get too far in the process. This will help

avoid situations where your tenant backs out at the last

ChApter 1 |RENTING YOUR PROPERTY

|

13

minute (he thought he could bring his three dogs and

your lease prohibits pets) and help minimize future

misunderstandings.

To put together a rental agreement or lease, see

Chapter 2. Once you’ve signed up a tenant and want

to clearly communicate your rules and regulations, see

Chapter 7.

Landlord Disclosures

California landlords are legally obligated to make

several disclosures to prospective tenants. You can add

the military, utility, and environmental disclosures to

the rental application or put them on a separate sheet

of paper attached to the rental application. A sample

form you can use to make written disclosures is shown

below.

FORM

You’ll fi nd a downloadable copy of the

Disclosures by Property Owner(s) form on the Nolo website.

See Appendix B for the link to the forms in this book.

You can also decide to make disclosures part of

your lease or rental agreement. (See Clause 27 in

Chapter 2.) The Megan’s Law disclosure must be on

the lease or rental agreement. (See Clause 26, State

Database Disclosure, in Chapter 2.)

Megan’s Law Database

Every written lease or rental agreement must inform

the tenant of the existence of a statewide database of

the names of registered sexual offenders. Members of

the public may view the state’s Department of Justice

website to see whether a certain individual is on

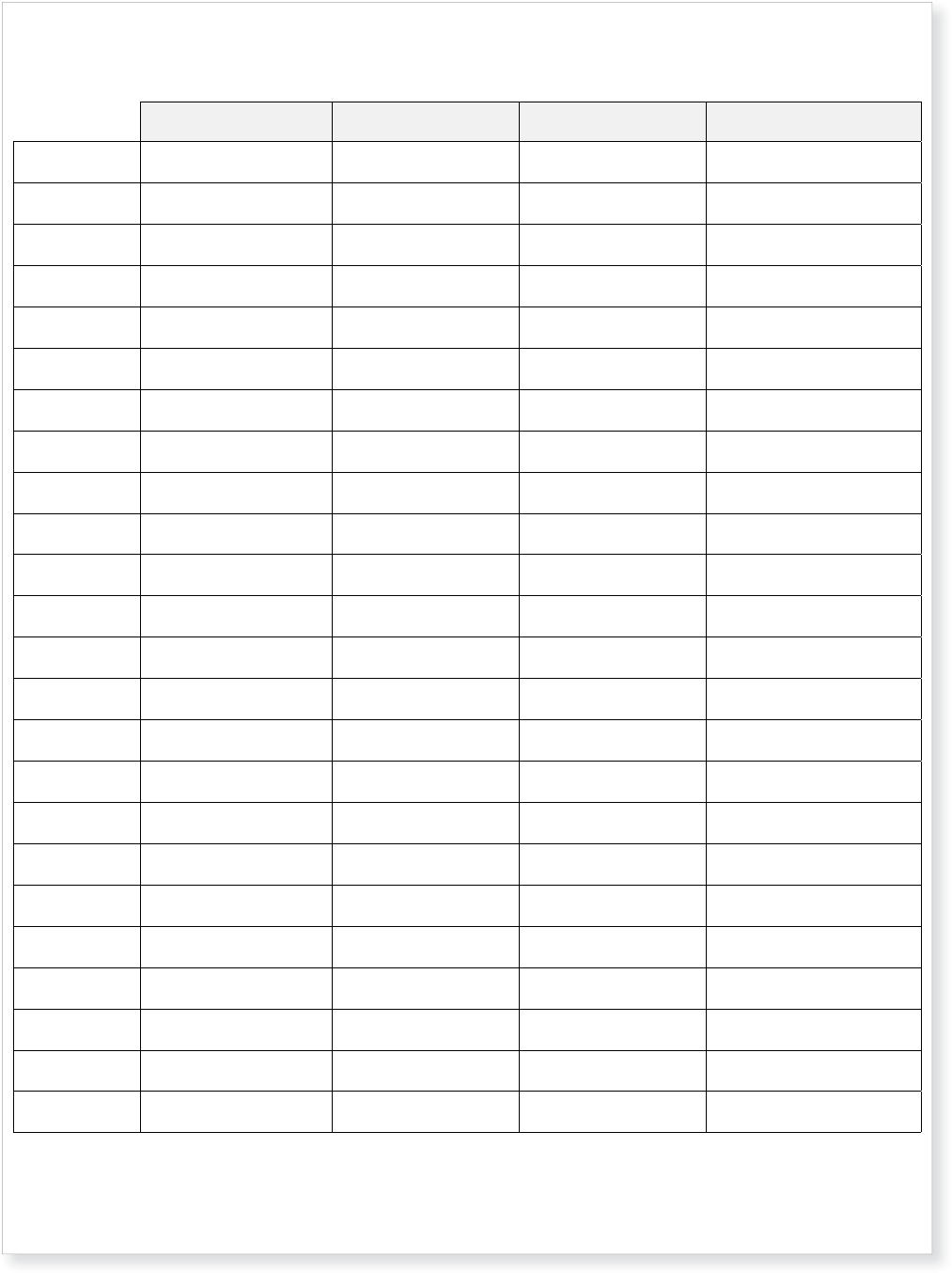

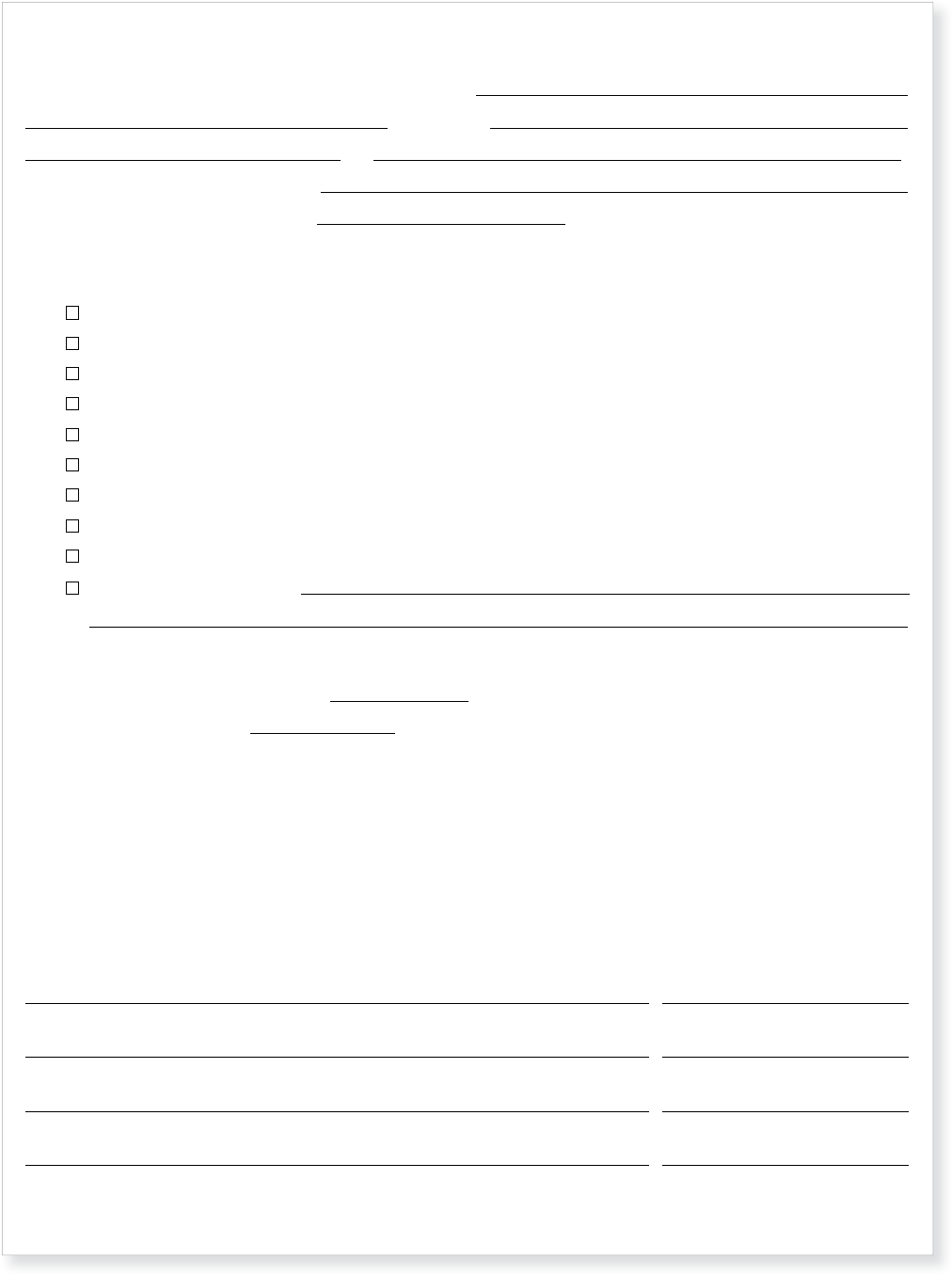

Application Screening Fee Receipt

is will acknowledge receipt of the sum of $ by

[Property Owner/Manager] from

[Applicant]

as part of his/her application for the rental property at

[Rental Property Address].

As provided under California Civil Code Section 1950.6, here is an itemization of how this $ screening fee will

be used:

Actual costs of obtaining Applicant’s credit/screening report $

Administrative costs of obtaining credit/screening report and checking Applicant’s references and background information

$

Total screening fee charged $

Date Applicant

Date Owner/Manager

42.00 Moe Manager

Terri D. Tenant

123 Polk Place #4,

Palo Alto, CA 94303

42.00

credit check and handling fee

25.00

17. 00

42.00

April 1, 20xx

Terri D. Tenant

April 1, 20xx Moe Manager

14

|

THE CALIFORNIA LANDLORD’S LAW BOOK: RIGHTS & RESPONSIBILITIES

the list. You must use the following legally required

language for this disclosure:

Notice: Pursuant to Section 290.46 of the Penal Code,

information about specified registered sex offenders

is made available to the public via an Internet Web

site maintained by the Department of Justice at www.

meganslaw.ca.gov. Depending on an offender’s criminal

history, this information will include either the address at

which the offender resides or the community of residence

and ZIP Code in which he or she resides.

Chapter 12 explains your duties under this law

in more detail. The rental agreement and lease in

Appendix C include this mandatory disclosure (see

Clause 16).

Location Near Former Military Base

If your property is within a mile of a “former ordnance

location”—an abandoned or closed military base in

which ammunition or military explosives were used—

you must notify all prospective tenants in writing.

(CC § 1940.7.) You can use the sample Disclosures by

Property Owner(s) form shown below to do this.

It is not necessary to warn prospective tenants of

the existence of current ordnance locations, such as

presently existing army or navy bases.

Although there are no penalties stated in the law

for failure to warn, and although the law applies only

to former ordnance locations actually known by the

owner, it’s only a matter of time before someone sues

their landlord for negligently failing to warn of a former

military base the landlord “should have known about.”

Therefore, if you have the slightest idea your property is

within a mile of a former military base or training area,

check it out. You might start by asking the reference

librarian at a nearby public library or by writing a letter

to your local Congressional representative. If you have a

particular location in mind, you can also check with the

County Recorder, who will show you how to trace the

ownership all the way back to the turn of the twentieth

century for any indication the property was at one time

owned or leased by the government.

Periodic and Other Pest Control

Registered structural pest control companies have long

been required to deliver warning notices to owners and

tenants of properties that were about to be treated as

part of an ongoing service contract—but the warning

notice had to be issued only once, at the time of the

initial treatment. This meant that subsequent tenants

would not receive the warning. Now, the landlord must

give a copy of this notice to every new tenant who

occupies a rental unit that is serviced periodically. The

notice must contain information about the frequency of

treatment. (B&P § 8538; CC § 1940.8.)

Landlords who apply pesticides on, in, or near a

rental building or unit (including a children’s play area)

whose occupant is a licensed day care provider must

provide advance written notice prior to doing so. See

“Family Day Care Homes” in Chapter 2.

Shared Utility Arrangements

State law requires property owners to disclose to

all prospective tenants, before they move in, any

arrangements where a tenant might wind up paying

for someone else’s gas or electricity use. (CC § 1940.9.)

This would occur, for example, where a single gas or

electric meter serves more than one unit, or where

a tenant’s gas or electric meter also measures gas

or electricity that serves a common area—such as a

washing machine in a laundry room or even a hallway

light not under the tenant’s control. We address this

issue in detail in Chapter 2. While you may use the

Disclosures by Property Owner(s) form shown below,

your lease or rental agreement is the more appropriate

place to disclose shared utility arrangements. (See

Clause 9 of our sample lease and rental agreement.)

Intentions to Demolish the Rental

If you plan on demolishing your rental property, you

or your agent must give written notice to applicants,

new tenants, and current tenants. (CC § 1940.6.) The

steps you must follow depend on whether you’re

notifying applicants, new tenants, or current tenants.

•Applicants and new tenants. If you have applied

for a permit to demolish their unit, you must

disclose this before entering into a rental agree-

ment or even before accepting a credit check

fee or negotiating “any writings that would

initiate a tenancy,” such as a holding deposit.

(CC § 1940.6(a)(1)(D).)

•Existing tenants (including tenants who have signed a

lease or rental agreement but haven’t yet moved in).

ChApter 1 |RENTING YOUR PROPERTY

|

15

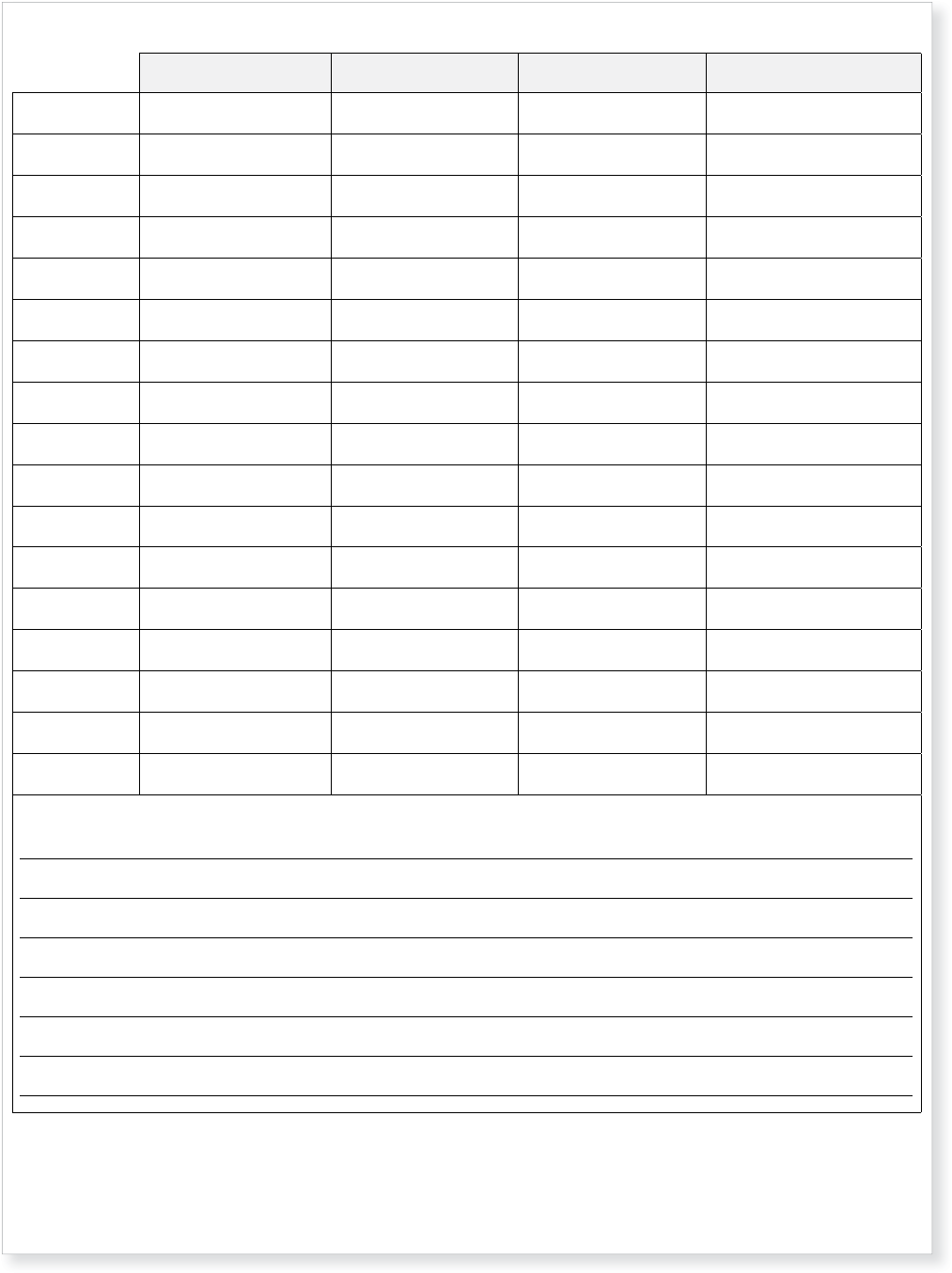

Disclosures by Property Owner(s)

e owner(s) of property located at

make(s) the following disclosure(s) to prospective tenant(s) and/or employee(s):

Date Owner’s Signature

I have read and received a copy of the above Disclosures by Property Owner(s).

Date Signature

Date Signature

1234 State Avenue, Apartment 5, Los Angeles, California

Location near former military base. State law requires property owners to disclose to all prospective tenants,

before they sign any rental agreement or lease, if the property they are seeking to rent is within one mile of a

former ordnance area (military base) as defined by California Civil Code Section 1940.7.

Details regarding the former military base near the property listed above are as follows:

Between 1942–1945, the U.S. Army used the nearby area bounded by 6th and 7th Streets and 1st and 3rd

Avenues in the City of Los Angeles as a reserve training area. Unexploded rifle ammunition has been found

there.

9/19/20xx Dry Wt

9/19/20xx Susan Johnson

9/19/20xx Thomas Johnson

16

|

THE CALIFORNIA LANDLORD’S LAW BOOK: RIGHTS & RESPONSIBILITIES

certain common areas. In Chapter 2, we explain how

to use Clause 25 to describe your policy.

Before you get to the point of negotiating a lease or

rental application with applicants, however, you may

want to tell them about your policy. You don’t want

complaints later from a nonsmoker who didn’t realize

that you permitted smoking in the common areas. Nor

do you want the complaint of a smoker who assumed

that smoking in an individual unit would be okay.

Local Disclosures

Check your local ordinance, particularly if your rental

unit is covered by rent control, for any city or county

disclosure requirements. To find yours, check your

local government website, or contact the office of your

mayor, city manager, or county administrator.

Checking Background,

References, and Credit History

of Potential Tenants

If an application looks good, the next step is to follow

up thoroughly. The time and money you spend are the

most cost-effective expenditures you’ll ever make.

CAUTION

Be consistent in your screening. You risk a charge

of illegal discrimination if you screen certain categories of

applicants more stringently than others. Make it your policy,

for example, to always require credit reports; don’t just get a

credit report for a single-parent applicant.

Here are six steps of a very thorough screening

process. You should always go through at least the first

three to check out the applicant’s previous landlords,

income, and employment, and run a credit check.

Check With Previous Landlords

and Other References

Always call previous landlords or managers for refer-

ences—even if you have a written letter of reference

from a previous landlord. Also, call previous employers

and personal references listed on the rental application.

To organize the information you gather from these

calls, use the Tenant References form, which lists key